-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Seitenstruktur

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

| THE Spitsbergen guidebook |

Home →

Yearly Archives: 2020 − News & Stories

No admissions to UNIS-courses for the rest of the year

UNIS has announced to not admit new students to courses for the summer and fall 2020 because of the Corona crisis. As there is so far no case of Covid-19 in Spitsbergen, the strategy is to make sure that those scientists and students who are already in Longyearbyen can continue with their work and education as normally as possible, and being (and staying) Covid-19-free does allow for a range of opportunities that UNIS wants to make use of.

Guest lecture by Maarten Loonen, the Ny-Ålesund-gooseman from the Netherlands,

at UNIS.

With this background, no new students will be admitted to regular courses for the rest of the year. A few exceptions will only be made under strict conditions for master and PhD-students who need to to fieldwork for their thesis.

Corona-quarantine extended

The Sysselmannen has announced that the compulsory quarantine will be extended until May 18 (18.00 hrs). It may be extended beyond this date if necessary.

This means that everybody who travels to Spitsbergen needs to stay in quarantine for 14 days, regardless of how one gets there and where exactly one arrives.

Health and emergency services might soon be in a difficult situation in case of a Covid-19 outbreak in Spitsbergen, so authorities are taking any further steps with great care. Considerations are currently being made for starting to open the school again and for the celebrations of the Norwegian national day on 17th May. This date was one of the reasons to chose the 18th of May as the minimum duration of the current quarantine regulations.

Applies to all of Spitsbergen: Corona-quarantine (photo composition).

At the same time plans are being made to return back to a – in a very wide sense – “normal” life again in society and economy. Authorities emphasise that this will be a long process that will require great care and may include setbacks. The importance of hygiene- and social distancing rules are highlighted and the public is requested to abstain from travelling to Spitsbergen unless necessary.

There are, as of now, no confirmed cases of Covid-19 in Spitsbergen.

Starting tourism up again in July?

Spitsbergen is currently almost completely closed to tourism. Only local inhabitants and Norwegians may come at all, theoretically also Norwegian tourists, but everybody has to stay in quarantine for 14 days unless an exceptional permission is given in special cases. The airline SAS is, however keeping the air traffic up, but there is mention of 10 flight passengers per day in average, and these will hardly be tourists. The airline Norwegian is currently planning to start flying again in June.

The shutdown does obviously have serious consequences for the local economy, including rising unemployment and calls for donations for example from small companies that have polar dogs, something that has, by the way, at least partly been successful to some degree.

Nobody knows when Spitsbergen will be open again for tourists. The further development of the pandemic will be decisive, as you may have guessed, and decisions have to be made on various levels.

Tourists in Longyearbyen: Nobody knows when they will return.

Now Longyearbyen’s mayor (lokalstyreleder) Arild Olsen has told Svalbardposten that he wants to consider opening up for tourism again in July, “possibly limited and we have to accept that it will be only Norwegian tourists, to begin with”, as Olsen says. Limitations in an area that is still remote and does not have large-scale sophisticated medical infrastracture will hardly surprise anyone, but limitations per nationality may rise an eyebrow, considering the Spitsbergen treaty.

But there is obviously still a way to go anyway before any tourists will return to Spitsbergen or other remote destinations.

Corona-crisis hits local economy beyond tourism

The Corona-crisis has hit Longyearbyen hard: tourism and service, both major factors for the local economy, have largely collapsed, leading to a high level of unemployment. Many fear losing their livelihood.

But also sectors outside tourism and service are affected: according to Svalbardposten, the mining company Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani AS has reduced the workforce in mine 7 near Longyearbyen by 8 people because the demand for industry coal has collapsed on the international market. These workers have already moved to Sveagruva to take part in the large clean-up that follows the end of coal mining there.

Coal mining in Spitsbergen is hit by the Corona-crisis

(archive image, Svea Nord).

Also a major customer of Svalsat (Kongsberg Satellite Services på Svalbard) has gone bankrupt due to the Corona-crisis, according to the website Highnorthnews: the global communications company Oneweb had the plan to provide the whole Arctic north of 60 degrees of latitude with high-speed, satellite-based internet. 648 satellites should have been part of that project, 74 of which have already been lifted up to the orbit since August last year.

Major ground infrastructure in high latitudes is needed to control the satellites and to transfer data both ways, services that are provided by Svalsat, a company that runs a large park of antennas on Platåberg near the airport in Longyearbyen. Oneweb hat a major contract with Svalsat. A number of antennas dedicated to the Oneweb project has already been built, there was mention of 60 Oneweb antennas in total on Platåberg.

Svalsat near Longyearbyen: also hit by the Corona-crisis.

The future of Oneweb and of the arctic internet project, including the large investments that have already been made, is uncertain.

Svalsat has a relatively small number of employees, but is itself an important customer for many other local companies. Svalsat has a number of other important customers, including large organisations such as ESA and NASA.

Corona crisis: small companies with dogs under pressure

The Corona virus has not yet come to Spitsbergen (as far as known at the time of writing). The strict quarantine rules are still in force, they have actually been extended on Friday (17 April) and will now last at least until 01 May, as the Sysselmannen informed.

As for economies all over the world, Longyearbyen is suffering severely from the economical consequences. Many companies and people depend on incomes derived within tourism. Unemployment has risen sharply to levels previously unknown at 78 degrees north.

Everybody has regular expenses and is under pressure to cover them, but some have even higher regular costs and this includes companies with polar dogs. Dogs need food and care even when there are now tourists. Current economical aid by the Norwegian government is amongst others aiming at helping companies with their expenses until May. But the current winter season is now coming to an end, and economically, the 2020 season just never happened, and the next winter season will not come any earlier than early 2021 – if it comes, that is. Companies have said that they will be happy if 2021 brings 60 % of a normal annual income.

Out on tour with dogs near Longyearbyen. Makes seriously happy!

And so does food for the dogs after the tour.

Some of the smaller companies have already appealed for help: Svalbard Husky have an appeal on their website, and Svalbard Villmarksenter have made an appeal in a local social media group, calling for “donations ear-marked dog-food”. Both are local family companies.

If you want to be a sponsor or godparent to a polar dog in Longyearbyen, then you are welcome to get in touch directly with either Svalbards Husky through their webseite (click here), via email (post@svalbardhusky.no) or give them a call: +47 784 03 078.

Or get in touch with Svalbard Villmarksenter through the webseite (click here), via email (info@svalbardvillmarkssenter.no) or on the phone: +47 79 02 17 00.

Martin Munck of Green Dog Svalbard, a larger company with 275 dogs, calculates 100,000 kroner per month just for dog food (currently near 8900 Euro). In a conversation with Svalbardposten, he strongly rejects rumours that killing dogs could be an option.

Corona crisis: many lost their jobs in Longyearbyen

The Corona virus hits economies hard everywhere in the world. Longyearbyen is no exception and the current crisis gives rise to a phenomenon that has so far been almost unknown up there: unemployment. Tourism and the service industry have largely collapsed and several hundred people have lost their jobs. According to official statistics, there were 9 people without jobs in Longyearbyen on 10 March, but already 261 on 23 March – the strongest increase in all of Norway, and the curve is still going up steeply. The actual number is supposed to be higher, because citizens of countries outside the European Economic Area (EEA) can not register as unemployed in Norway.

The fact that unemploymentship has been virtually unknown in Longyearben is not only due to the good economical situation. Actually, recent years have seen the collapse of large parts of the coal mining industry and a lot of jobs were lost in this process. On the other hand, tourism and science have developed positively. But the background is another one, which has to do with the Spitsbergen Treaty which recently became 100 years old: the treaty gives citizens from signatory countries the same individual rights as Norwegians. Everybody can live and work in Longyearbyen without asking for permission.

But this freedom has a price tag: there is no social system that takes care of everybody. Essentially, everybody is responsible to take care of him- or herself. If you can’t finance you life in Spitsbergen, then you have to leave. Five persons have been expelled by the authorities since 2017 because they were not able to support themselves financially. Four out of these five were expelled before 2020, so there is no connection to the recent crisis.

In other words: if you can’t afford to live in Longyearbyen then you are not going to stay long, so there has not been unemployment on any significant level until recently. If you needed public support, then you had to rely on the social systems of your home country, many of which may not support citizens living abroad or only to a degree that will not make much of a difference as Longyearbyen is a very expensive place.

This is, in principle, not going to change: Norway is generally neither obliged nor willing to take responsibility for citizens of third countries who are getting in difficulties in Longyearbyen. On the other hand, the current situation is acute. Longyearbyen has a very international population. There is, for example, a significant number of people from Thailand who came to Longyearbyen years ago to live and work there. Many have typically jobs in restaurants or other service industries that have now collapsed. Many can hardly expect much support from their original home countries, and returning there may also not be an option easily available to everyone as many have given up there homes there years ago, plus the impossibility to travel anywhere these days.

Longyearbyen during the Corona-crisis: dark times, even though it does not get dark anymore in reality and the sun will soon shine 24 hours a day.

So there are many people now in Longyearbyen who don’t have an income. There are estimates of near 300 people. Measures are taken now in Longyearbyen (Lokalstyre) to offer public help to citizens from third countries outside the European Economic Area. These measures come with a time limited, but there is clearly need for action right now. In the future, companies in Longyearbyen may have to install social insurance systems for their non-Norwegian employees, but right now the present situation needs to be dealt with. There have already been private aid appeals for families in difficulties, especially for people who moved to Longyearbyen less than 6 months ago because they are supported only for 20 days in the current Corona crisis package by the Norwegian government. Those who have been in Longyearbyen more than half a year will be supported until 20 June.

Longyearbyen Lokalstyre (community council) has applied for 178.5 million kroner from the Government in Oslo to support the local economy. This may include goods and orders that can be delivered quickly by local companies, financial relief for inhabitants by cutting fees for example for water, power and long-distance heating, all of which is very expensive in Longyearbyen and to compensate for losses expected in the economy of the community. Just the cancellations by large cruise ships for this year will probably cost more than 20 million kroner in harbour fees that will be lost.

Just as anywhere in the world, nobody in Longyearbyen has got an idea when and how the situation will normalise again.

Monthly temperature in March below average

The weather statistics from Longyearbyen have, for years on end, yielded temperatures above the long-term average. This has been the case for 111 months, a series that started in November 2010: since then and until February 2020, there has not been a single month with an average temperature below the long-term statistics.

But March 2020 turned out to be the month that finally breaks up this series of more than 9 years. It is very unlikely to be a new trend, just a cold month between many warmer ones, but still – the monthly average of March 2020 was -16.2°C or half a degree below the long-term average, according to Ketil Isaksen from the Norwegian meteorological institute.

A cold March: fresh ice forming in Adventfjord near Longyearbyen.

Half a degree below average is not exactly an awful lot, but nevertheless Isaksen assumes that the cold winter gives the warming permafrost a little break: because of the thin snow cover, the cold should have penetrated the ground, an effect that should last a while into the summer.

The reference period for the long-term average is 1960-1990. As soon as the current year is over, there will be a new reference period: 1990-2020. This will increase the reference average temperature values because these recent decades have been significantly warmer than the previous ones. Hence, as the new reference value will then be higher, we will, in the future, see more months again with average temperatures below the long-term average: a result of the new statistical base rather then the end of climate change with will keep making the Arctic warmer. This is, based on all current knowledge, not going to change any time soon. The meteorological record from Longyearbyen airport (Svalbard Lufthavn) shows that the temperature has risen by no less than 5.6 degrees since 1961!

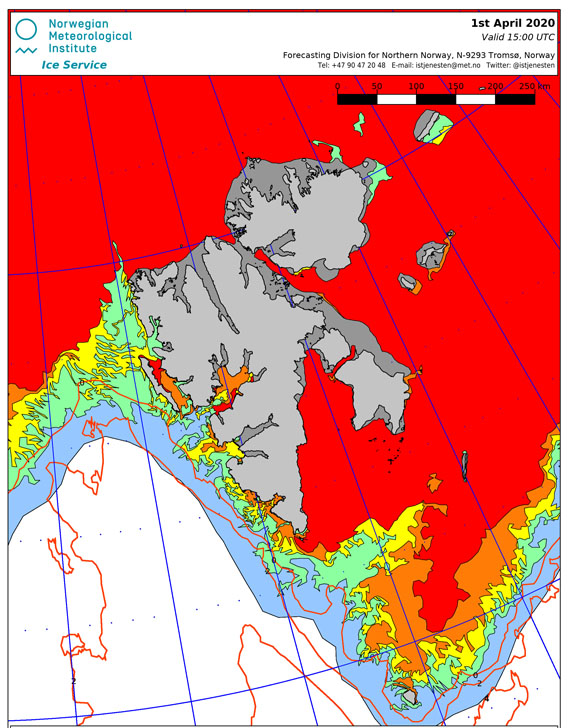

Ice chart as of 01st April 2020. No April Fool’s Day joke, but quite a lot of ice.

© Norwegian meteorological Institute.

Currently, we can at least enjoy the fact that there is a good ice cover in and near Spitsbergen, both fast ice in coastal waters and drift ice, currently reaching as far south as Bear Island (Bjørnøya)!

Polar bear died from circulatory collapse

The female polar bear that was anaesthetised near Longyearbyen in late January and that died during helicopter transport is found to have died from circulatory collapse as a consequence of a combination of stress, shock and medication, according to the Sysselmannen.

Sysselmannen (police) and Norwegian Polar Institute experts had started to scare the polar bear away from Vestpynten near Longyearbyen by helicopter in the late afternoon of 30 January. The bear was moved across Adventfjord and – partly by using snow mobiles – into a side valley, where she was finally anaesthetised. A total of 2.5 hours passed from the beginning of the operation until she was put to sleep: a long time for an animal that is not made to run fast over longer distances. It is for good reason that nobody is generally allowed to follow a polar bear that has changed its behaviour so it might be at risk.

This seems to be exactly what happened in this case, considering a chase over 2.5 hours by helicopter and snow mobile (there is mention of a short rest which is included in that time span), although “polar bear expertise” was present in shape of an expert from the Norwegian Polar Institute. The procedure was obviously too much for the bear, who received further medication after the initial aenesthetisation and died in the helicopter during transport to Kinnvika on Nordaustland.

Polar bear family: mother (left, in front) and two second year cubs in good shape.

Mid August, Edgeøya.

The bear was a female with a very low weight of 62 kg. It is believed that she was a first year cub or a very small second year cub. In either case, she should still have been together with her mother.

Corona-virus: Spitsbergen in lockdown-mode

After a lucky return from Antarctica, the only continent currently not directly affected by the Corona-virus (but certainly indirectly), I am now about to catch up with the Spitsbergen news on ths site. It is not that nothing has happened up north. To start where I stopped a few weeks ago: the coal mine Svea Nord was indeed officially closed with a little ceremony on 04 March, putting an end to a good 100 years of mining history in Sveagruva.

I’ll get back to other issues over the next couple of days. Now, the one thing that keeps the world busy and in awe: the Corona-virus – what else? So far, the virus has not reached Spitsbergen. But it will not be possible to keep the settlements fully isolated from the rest of the world forever. The question is, as anywhere, how to controll this transition – if a controlled transition is possible at all.

So far, the idea is to keep all settlements as isolated as possible to protect the local population from the virus. Tourism has come to a complete stop. Everybody who is now travelling to Spitsbergen has to remain in 14 days of quarantine. Exceptions can only be made by the authorities under strict conditions if requested by the employer or an institution. Generally, only Norwegian citizens, residents or people with a work permit (does not apply in Svalbard, but you would need to have a good professional reason to travel up there right now) are allowed in.

Snow mobiles in Longyearbyen: currently silenced by the Corona-virus.

This will clearly have a significant impact on the local economy: March and April are usually high season within tourism. Hotels and activities are usually fully booked. Currently, however, many companies and jobs in the service industry are at risk, and many guides have already left the island, waiting for better times in their home countries which are usually cheaper places to stay.

This is now in force until 13 April but may be extended. The future development remains to be seen, also with regards to the summer shipping season.

Spitsbergen, the Antarctic and the Corona virus

The winter season should be super busy at this time in Spitsbergen, but instead it is very silent now in Longyearbyen and Barentsburg. No tourists there at all. The only thing that you might hear is the tourism industry crying.

And on this blog and news site: also nothing at the time being.

The Antarctic is the only corona-free continent, but that does not mean that it does not affect us here in the south. We have now been to the Antarctic for a while and I am still far south with Ortelius. So I guess that I am currently the last one in the world who gets any news that seem to be changing by the minute and hence it would probably be silly to post any „news“ here.

But I did and do still write about our journey here in the south, in the blog on www.antarctic.eu. Also here, the Corona virus currently governs the world. No, not directly. We on Ortelius are all well, health-wise. But it sends us on a strange journey. Not as planned back to the Antarctic Peninsula, but up north and back home. Slowly and with quite a few extra twists and bends that we still need to find out about. Read more in my antarctic blog.

Svea Nord is history

Svea Nord was the largest coal mine ever in Spitsbergen. It belonged to the mining complex of Sveagruva in Van Mijenfjord, together with the settlement of Sveagruva itself, the harbour facilities at Kapp Amsterdam and the mine in Lunckefjellet.

The mine was opened in 2001. A coal seam thickness of up to 6 metres allowed an annual production of 3 million tons. Not recordbreaking on a global scale, but the largest amount that was ever achieved in any mine in Spitsbergen. This put the mining company Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani in a good economical situation for some years around 2008.

The longwall-method could be used very economically in Svea Nord with a coal thickness of 4-6 metres.

Then, prices on the world markest went downhill and the economical situation became difficult for the coal mines in Spitsbergen. Job cuts and a struggle for funding further mining operations were the theme of the day in 2013 and following years. The Norwegian government, owner of Store Norske, helped initially out but then decided in 2015 to put mining in Sveagruva on hold. In 2017 the decision followed to abandon all mining activities there altogether, including a removal of the mines and the settlement – a unique step in the history of Spitsbergen.

The mine in Lunckefjellet was closed already in early 2019. This mine was ready for productive operation in 2013, but the productive stage was never actually reached in Lunckefjellet.

Tunnel in Svea Nord, with mining equipment ready to be removed before the mine is closed.

Now the large mine of Svea Nord is about to be closed. A lot of materials and equipment have been removed and will be shipped out. According to the plan, Svea Nord will be closed for good in March 2020.

At the same time, the clean-up of the settlement of Sveagruva is making progress. Apart from a few old artefacts that are protected as part of the historical heritage of the area, everything is supposed to be removed. In the end, only careful observers should be able to see that people lived here for decades and that this area was the site of industrial mining for almost a century. But there is still a way to go. Closing Svea Nord is a significant step within this process, and it is quite unique in the context of arctic mining: in the 20th century, it was common just to leave things just where they were unless they were valuable enough to remove them.

The very last pieces of coal that have left Svea Nord will serve scientific purposes. Geologist Malte Jochmann and mining engineer Kristin Løvø at work (December 2019).

In December 2019, I had the opportunity to visit Svea Nord together with a team of geologists. While they were taking smaples, I had the chance to do some photography, capturing some impressions of Spitsbergen’s largest coal mine. As a result, I have created a page with photo galleries and panoramas of Svea Nord to make it at least virtually accessible for everybody while the mine is physically closed and inaccessible forever. There is actually a set of several pages, also including Sveagruva (settlement), Lunckefjellet (mine) and Kapp Amsterdam (harbour). They are all accessible through an overview page Svea area (click here).

Avalanche accident at Fridtjovbreen: two persons dead

Two people, both of German nationality, were killed during an avalanche accident at Fridtjovbreen, a glacier south of Barentsburg. Both were travelling as part of a guided group of the Arctic Travel Company in Barentsburg. When Norwegian rescue forces arrived on the scene, they could only declare both persons dead.

The Norwegian authorities are informing the relatives of the victims and will investigate the accident. The community of Longyearbyen has established a crisis team to help all people in Barentsburg and Longyearbyen who might be in need.

Polar bear weighed only 62 kg

The polar bear that died in late January during transportation in a helicopter weighed only 62 kg as first results of the post mortem revealed. This means that the bear must either have been very small or extremely thin. Even a small, sub-adult female should have more than 100 kg. Even a second year cub should weigh significantly more than 60 kg, and it should still be with its mother then. A first year cub would not be able to survive on its own, without the mother.

Also chances for survival for a (sub)adult polar bear with a weight of only 62 kg would have been doubtful at best.

This is currently, however, speculation. Further details of the post mortem, which will hopefully enable specialists to draw conclusions regarding the cause of death, will only be available in several weeks.

Young polar bear together with its mother. The little bear was about 20 months old at the time the picture was taken and its weight was certainly well above 60 kg.

There is also new information regarding the polar bear visits to Longyearbyen in late December: DNA analysis of various samples revealed that it were at least two individuals who came close to and into the settlement then.

100 years Spitsbergen Treaty

The Spitsbergen Treaty was signed exactly 100 years ago, on 09 February 1920, in Versailles. The contract secured suverenity over the Spitsbergen islands but includes several limitations. Click here to read more about the treaty itself on the page dedicated to the treaty within this website.

Fredrik Wedel Jarlsberg, Norwegian ambassador in Paris,

signs the treaty on 09 February 1920 in Versailles.

The Spitsbergen Treaty was negotiated over several months in Versailles in 1919. Fredrik Wedel Jarlsberg was leading the negotiations on behalf of Norway, but others including Fridtjof Nansen had been part of the political work that had paved the way to the treaty over years.

Today, the treaty is often referred to as the Svalbard Treaty, but the original treaty text does not include the word “Svalbard” at all.

Overlapping private territorial by a number of mining companies from various countries had to be sorted before the treaty could enter force. This happened finally on 14 August 1925, when the “Svalbard law” (Svalbardloven) came into force in Norway, turning the treaty into national law.

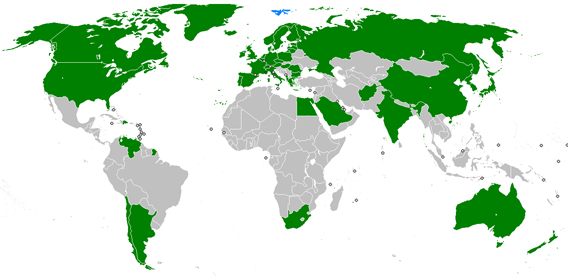

The treaty is still in force. There are some disputes regarding the use of marine resources (fishing, oil, gas, other mineral resources) outside the 12 mile zone, but within the 200 mile zone around Svalbard. The concept of these zones was defined much later and they were not part of the treaty, which hence leaves room for different interpretations, depending on whom you ask. Norway claims that the principle of nondiscrimination (equal rights for everybody regardless of nationality) is valid only within the 12-mile zone, but claims exclusive rights in the 200-mile economical zone (outside the 12-mile zone). Other countries do not agree, namely Latvia which was up to now the last country that entered the Spitsbergen Treaty on 13 June 2016 (a few months after North Korea) and Russia. Russia’s ministry of foreign affairs has just recently again released a press note claiming to be unhappy about restrictions of Russian activities in Spitsbergen and expects Norway to accept bilateral talks, something that Norway has never accepted in the past.

Signatory countries in the Spitsbergen Treaty.

Today, 100 years after the treaty was signed in Paris on 09 February 1920, a number of events and lectures are dedicated to the treaty in Longyearbyen, Norway and other countries.

Anaesthetised polar bear died during transport

The polar bear that was anaesthetised and flown out last night died during the transport in the helicopter, according to the Sysselmannen.

The cause of death is currently unknown. A postmortem examination is expected to clarify this within a few days.

An anaesthetised bear during preparations for a helicopter flight to Nordaustland (archive image, 2016).

The bear is said to have been a female that was not tagged.

There is always a remaining risk inherent to anaesthesy, especially as the weight and health condition of the “patient” are mostly unknown or can, at best, be roughly estimated, something that must obviously have been difficult last night in darkness.

Anything beyond this is mere speculation at the time being until the results of the postmortem are available.

News-Listing live generated at 2024/April/25 at 04:58:55 Uhr (GMT+1)