-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

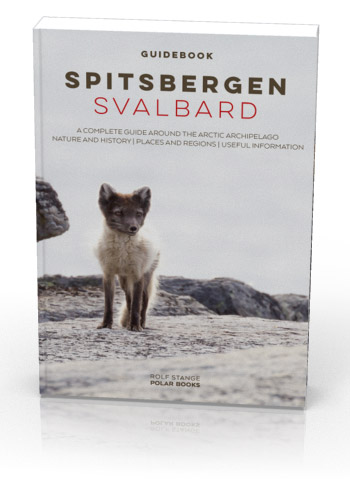

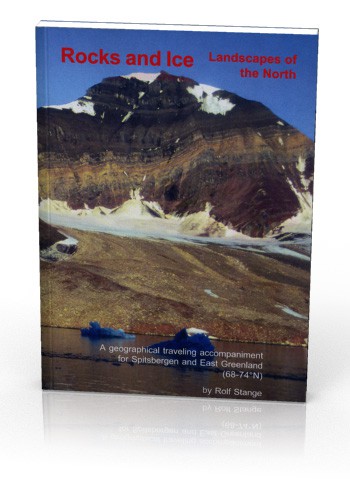

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Seitenstruktur

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

| THE Spitsbergen guidebook |

Home → * News and Stories → Cod war between Norway and EU about to escalate

Cod war between Norway and EU about to escalate

A new “cod war”, a conflict about fishing rights, has been lurking in the Barents Sea already for some time. The problem is a disagreement about cod quotas for European fishing ships in the 200 mile zone around Svalbard. The matter is complex.

The problem: EU fishing quotas after the Brexit

On the surface, the problem appears to be new quotas for European fishing vessels that Norway has set after the Brexit by deducting the British quota from the European allowance. The new European quota amounts to 17,885 tons, according to NRK, while British fishing vessels are afforded a quota of 5,000 tons. The EU, however, is not happy about this new quota and reacted by allocating themselves a quota of 28,431 tons, something that is not accepted by Norway. The EU accused the current Norwegian fishery policy of being arbitrary and discriminatory.

Both sides have now verbally rigged up, both saying they are prepared to take steps as necessary to take care of their rights. Norway has made clear that coastguard and police are ready to take the usual steps in case they find fishing vessels with illegal catch in their waters, including confiscation of ships and catches and arrestation of crews. It was Lars Fause, chief prosecutor in north Norway, who said this. Later this year, Fause will follow Sysselmann Kjerstin Askholt in Longyearbyen as the first one to bear the gender-neutral title Sysselmester.

Yummy cod taken in Isfjord.

The conflict between the EU and Norway is, however, about other volumes.

Key problem: the Spitsbergen Treaty

But the essential problem is hidden in the paragraphs of the Spitsbergen Treaty. The second article of the treaty guarantees that “Ships and nationals of all the High Contracting Parties shall enjoy equally the rights of fishing and hunting in the territories specified in Article 1 and in their territorial waters.” The problem is the definition of “territorial waters”. The Spitsbergen Treaty was signed in 1920. Until then, most countries looked upon coastal waters within 3 miles (a gun shot) as their territorial waters. It was not before 1921 that governments began to include the waters as far out as 12 miles into their own territory. Until today, this is not everywhere as clearly defined as one might think or wish, but as far as this, there is consensus in the area in question: everybody agrees that the Spitsbergen Treaty is valid within the 12 mile zone (territorial waters) around Svalbard, meaning that fishing ships of all treaty parties enjoy equal rights there.

The problem starts when it comes to the exclusive economic zone (EEZ), which stretches as far as 200 miles from the coast. Hence, the EEZ is much larger and includes large and valuable biological resources. The EEZ was, however, not defined in internatinal law before 1982, when the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea was concluded.

Based on article 1 of the Spitsbergen Treaty, Norway claims “full and absolute sovereignty” also of the large exclusive economic zone (200 mile zone), but insists at the same time that article 2 ot the same treaty, which gives all treaty parties equal rights, is not valid there. In contrast, Norway claims exclusive rights in the EEZ. It does not really surprise that there are those treaty parties who do not agree with this position.

The coastguard guarantees Norwegian sovereignty in the waters around Spitsbergen. Unfriendly encounters of coastguard vessels and EU fishing vessels may be coming up.

The Spitsbergen Treaty and the “exclusive economic zone (EEZ)”

Whatever one’s position is on the question wether or not the Spitsbergen Treaty and its fundamental principle of equal rights and access (non-discrimination) is to be applied in the EEZ, there can hardly be any doubts that fishing vessels from the EU or third countries need to respect Norwegian economical rights in these waters. The question is, however, how Norway may balance the quotas that are allocated to foreign fishing vessels relative to their national quotas: according to the principle of non-discrimination (if article 2 of the Spitsbergen Treaty is to be applied) or exclusively.

A complex matter. What is clearly missing is an authority accapted by all sides that could decide on such matters of interpretation regarding the Spitsbergen Treaty. Norway insists to possess the exclusive authority to such questions, but that is not accepted by Brussels.

While there is political and juridical need for clarification, both the Norwegian coastguard and European fishing vessels are getting prepared and conflicts are to be feared. The staggered observer keeps watching and wondering.

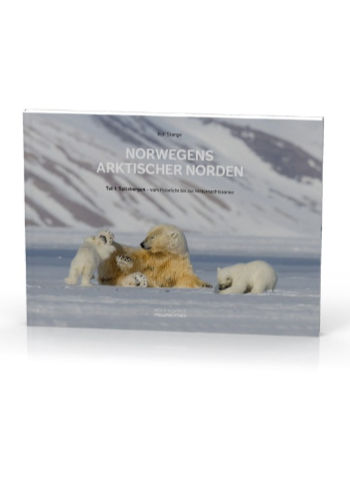

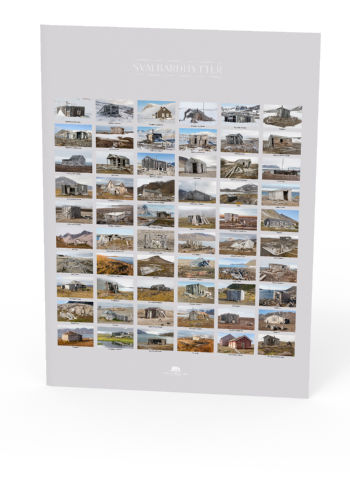

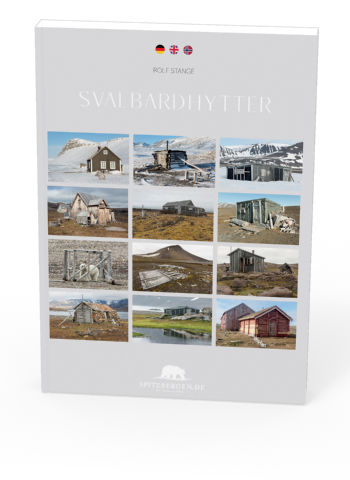

BOOKS, CALENDAR, POSTCARDS AND MORE

This and other publishing products of the Spitsbergen publishing house in the Spitsbergen-Shop.

last modification: 2021-04-22 ·

copyright: Rolf Stange