-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

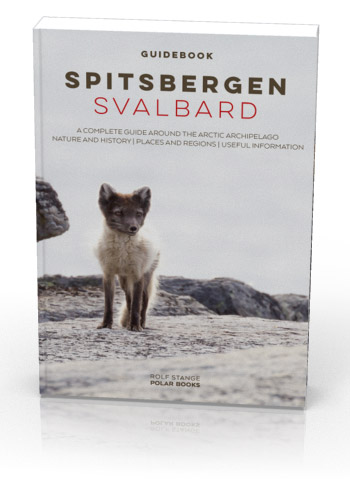

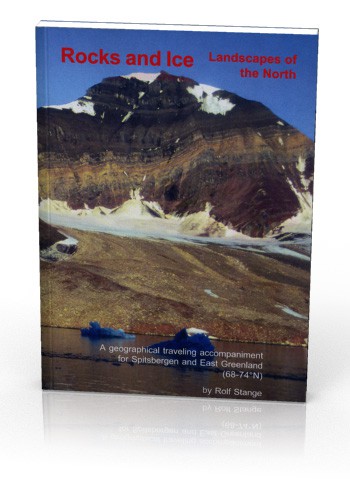

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Seitenstruktur

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

| THE Spitsbergen guidebook |

Home → * Photos, Panoramas, Videos and Webcams → Spitsbergen Panoramas → Ekmanfjord: Coraholmen

Ekmanfjord: Coraholmen

360°-Panorama

- pano anchor link: #Coraholmen_12Juni13_43

The little island of Coraholmen is a jewel in terms of scenery and natural history. It is surrounded by impressive mountains including Kolosseum (highest part visible: 605 metres) and Kapitol (858 metres). This may not seem to high, but these mountains are not just nevertheless impressive and beautiful, but simply unique in terms of their appearance and character.

The same holds true for Coraholmen. For millenia following the last major glaciation (something like 10,000 years ago, or a bit more), the island had been a flat, green tundra island, until the glacier Sefströmnbreen advanced rapidly and strongly in the late 19th century, turning Coraholmen’s western part into a chaos of moraine hills and muddy ponds. The red-coloured sandstone (devonian Old Red) in the catchment area of Sefströmbreen is responsible for the lovely reddish colour. Shells and colony of calcareous algae, similar to corals, make it very clear that the glacier picked up some bits and pieces of fjord bottom and marine sediment already on the island (raised beaches) before mixing everything up into a huge moraine landscape. Hence, it is possible to reconstruct quite a bit of landscape evolution: starting with the deposition of the devonian Old Red almost 400 million years ago, through the ice-age glaciation, followed by the formation of raised beaches (still present on the eastern part of Coraholmen) by post-glacial counter-isostatic land uplift (not clear? Read Rocks and Ice), glacier advances during the 19th centuries Little Ice Age and the pronounced retreat since then.

And there is, of course, wildlife. Arctic terns, geese and ducks in large numbers. You have to exercise great care while moving around during the breeding season. There are Red-throated divers on some of the ponds, and in 2013, we had a wonderful encounter with a rare Sabine’s gull on Coraholmen.

Coraholmen has a slightly smaller neighbour, Flintholmen, which has gone through the same history and is accordingly similar in terms of landscape and appearance.

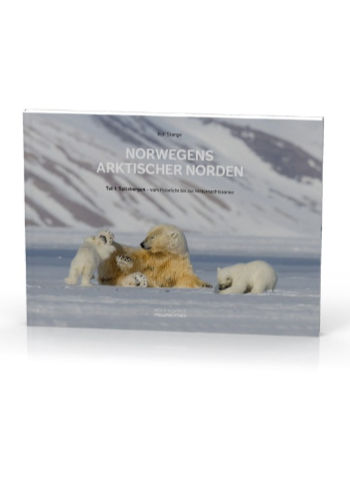

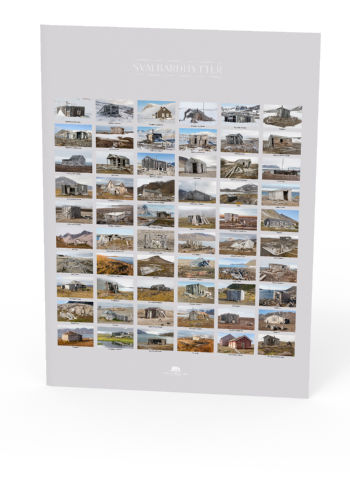

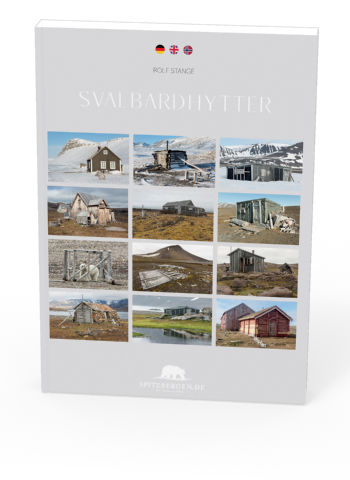

BOOKS, CALENDAR, POSTCARDS AND MORE

This and other publishing products of the Spitsbergen publishing house in the Spitsbergen-Shop.

last modification: 2014-06-05 ·

copyright: Rolf Stange