-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

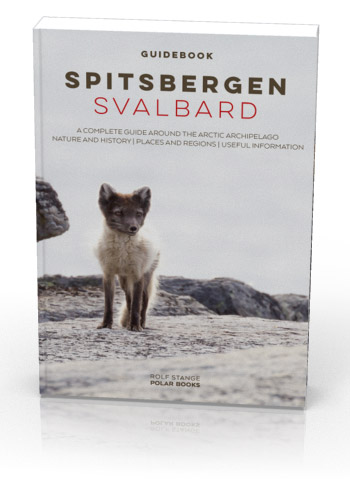

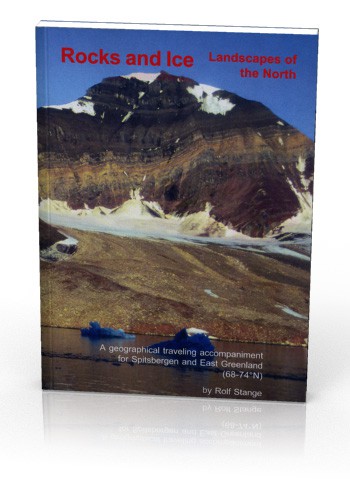

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Seitenstruktur

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

| THE Spitsbergen guidebook |

The Spitsbergen Treaty

History of Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen was no man’s land until the early 20th century. Several nations in northern Europe had occasionally been interested, but not to a degree that made it worthwhile to negotiate the issue seriously. Most were happy to keep the archipelago no man’s land; as long as nobody else achieved control, it was not important enough to raise interest in political circles and to risk disputes with other countries. Most resources such as whales and fishing were rather independent of the actual land area anyway.

Things changed in the late 19th and early 20th century, when mining became the dominating field of economy in Spitsbergen. Suddenly the question of land control became important, especially there was a demand for reliable administration and legislation. Various options were discussed, such as a joint administration of Spitsbergen by its nearest neighbours Norway, Sweden and Russia.

The first world war drew interest away from the Arctic. During the peace conferences in Paris, the Norwegians could convince other nations to put Spitsbergen under Norwegian souvereignty. This was formally done with the Spitsbergen Treaty, which was signed on 09 February 1920 in Versailles (the term “Svalbard” was not used until later. Today, the treaty is commonly referred to as “Svalbard Treaty”, but this term is not historically correct).

Fredrik Wedel Jarlsberg, Norwegian ambassador in Paris,

signs the treaty on 09 February 1920 in Versailles.

In 1925, the treaty came into force and was included in Norwegian law. The “Svalbard law” (this is where the term “Svalbard” came in) came into force on 14 August 1925. This day is considered Svalbard’s national day in Longyearbyen.

But Spitsbergen did not become a part of Norway just as any other part of the mainland. The treaty defines several frame conditions, such as

- Spitsbergen is under Norwegian administration and legislation.

- Citizens of all signatory nations have free access and the right of economic activities.

- Spitsbergen remains demilitarized. No nation, including Norway, is allowed to permanently station military personell or equipment on Spitsbergen.

In practice, this has not alway been easy. Especially the definition of what is or is not military has been difficult on occasions. In 1975, the opening of the airport near Longyearbyen raised protest of the Sovjet government, which stated that the airport could be used for military purposes. Facilities to launch research rockets have to be removed after every rocket launch. In the Russian settlement Barentsburg, the size of the helicopter fleet and the helipad has at times had a size far beyond the actual needs of a mining settlement and company.

Regarding military presence, “permanent” is an important term that should not be overlooked. Norway’s coast guard is regularly present in Spitsbergen’s waters, executing Norwegian sovereignty. The Norwegian coast guard is part of the navy and thus a branch of the military (in Germany, it is a police force, not military). Article 9 of the treaty says “… Norway undertakes not to create nor to allow the establishment of any naval base in the territories specified in Article 1 and not to construct any fortification in the said territories, which may never be used for warlike purposes.” Non-permanent military presence is obviously not automatically a breach of the treaty, such as the regular presence of the Norwegian coast guard or the occasional presence of a Norwegian frigate, but Norwegian politics keep Norwegian military activities in Spitsbergen on a low profile. Foreign armed forces are, however, obviously a different question. In 2016, Chechen special forces were suddenly seen on the airport in Longyearbyen, on their way to a military exercise in the area of the Russian ice Camp Barneo, close to the North Pole. This was certainly not met with great public sympathy, but even Norwegian officials commented that this was probably not a breach of the Spitsbergen Treaty. In the Svalbard White Paper of 2008-2009 (chapter 3.1.5, section C, page 23 of the pdf version), the Norwegian government makes it pretty clear that any foreign military activity in Svalbard is prohibited and would be seen as a severe breach on Norwegian sovereignty (“Enhver fremmed militær aktivitet på Svalbard er forbudt og ville innebære en grov suverenitetskrenkelse.”)

The treaty has served its purpose altogether well. It is the only one of all the treaties signed in 1920 in Versailles that is still in force and it is not substantially questioned by anyone, although there are critical voices concerning particular issues. Russia has occasionally rumoured that Spitsbergen might become a source of conflict, potentially even leading up to a war, according to the Barentsobserver in an article from 2017. Drastic words! This perspectiv is obviously not shared by Norway or any other treaty party.

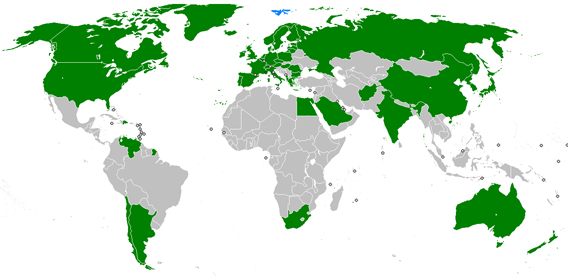

But – there has been criticism. Pretty much the only aspect today where most governments disagree with Norway is the situation regarding the territorial waters. According to Norway, within the coordinates that define the treaty area, only the territorial waters are governed by the treaty regulations, that is the twelve mile zone (four miles until 2004, then the zone was re-defined). According to Norway, the waters outside the twelve mile zone, but within the exclusive economic zone (200 miles) are exactly that – an exclusive economic zone where Norway can limit the rights of any third party. It is not surprising that other governments and their citizen’s companies with interests in fisheries, oil and gas do not necessarily agree with this. Amongst the governments that have expressed disagreement are Latvia, who entered the Spitsbergen Treaty as the currently last country on 13 June 2016 (a few months after North Korea) and Russia..

Signatory countries in the Spitsbergen Treaty.

An additional contract or possibly a verdict by the International Court of Justice in The Hague might sort this out, but Norway’s position is that the existing treaty is clear and there is no need for further negotiations or agreements.

Russia is the only nation next to Norway which makes use of the right of mining. The settlements on both sides suspiciously kept an eye on each other during the cold war, but co-existed peacefully. Today, there are regular official and private contacts.

Click here for the English version of the Spitsbergen Treaty (pdf). This is a version that was modified by the Norwegian ministry of justice in 1988 – as mentioned, the original text does not know the term “Svalbard” at all. For the rest, the text is as signed in 1920.

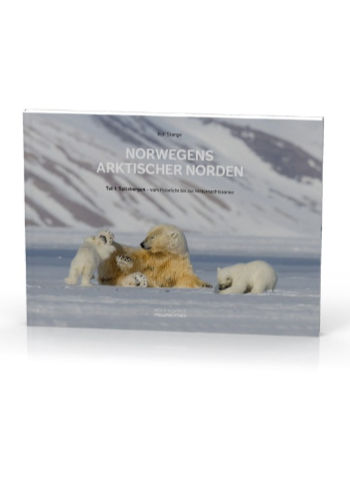

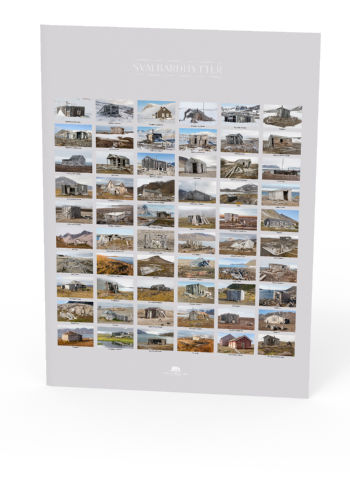

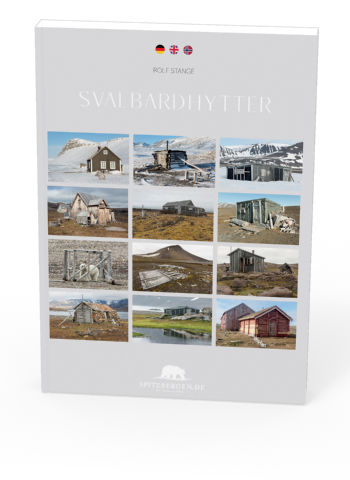

BOOKS, CALENDAR, POSTCARDS AND MORE

This and other publishing products of the Spitsbergen publishing house in the Spitsbergen-Shop.

last modification: 2020-02-12 ·

copyright: Rolf Stange