-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

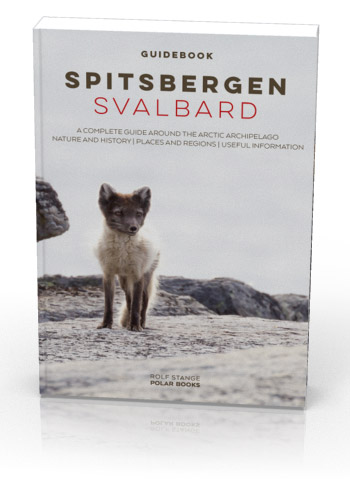

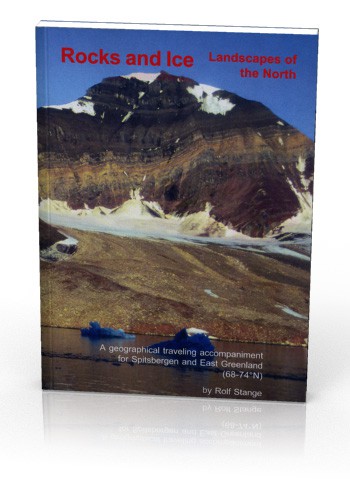

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Page Structure

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

-

Newsletter

| Guidebook: Spitsbergen-Svalbard |

Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus)

Walrus, Hinlopen Strait.

Description: The Walrus is the largest seal species in the Arctic and the second-largest one on a global scale; only male Elephant seals outgrow Walrus. The tusks, that can be up to one metre long, make them unmistakable; tusks of Walrus cows are slightly smaller than those of bulls. Bulls can be up to 3.5 metres long and 1,500 kg in weight, while cows reach 2.5 metres and a weight of 900 kg. A newly born Walrus baby is 1.3 metres long and weighs sweet 60-85 kg. The Pacific Walrus (O. r. divergens) is slightly bigger than its Atlantic relative. Both are considered subspecies of the same species.

The colour is brown, but variable: Once they have spent some hours ashore, the skin tends to have a pinkish shade, especially in warm weather, as an increased blood circulation in the thick skin prevents overheating. When they come out of the water or if it is cold, they decrease blood circulation to preserve heat; then they will appear almost dark-grey.

Telling the sexes apart is difficult. Adult males are significantly larger than females. Males have got more scars and characteristic calluses around the neck, whereas the cows have smoother skin.

Walruses near Lågøya. At least the one to the right is quite clearly a male.

The significance of the tusks is not clear. It is known that they are not needed to obtain food. They are certainly useful for defence against Polar bears, although this is rarely needed, and for climbing up on ice floes. The most important purpose is certainly as a status symbol and weapon for fighting during the mating season. The tusks may break off, which certainly affects the breeding status of males, but it does not influence life expectancy.

Walrus with only on tusk in Isfjord.

Walrus are very social. Single animals are the exception. They stay in groups, often with more than 20 individuals. Herds of more than 100 animals are not the rule in Svalbard, but such large or even larger groups do occur.

Distribution / Migration: Walrus occur in several areas around the Arctic. There are several, more or less isolated populations in northeastern Canada and West Greenland as well as northeastern Siberia and the Bering Strait. The Atlantic Walrus is spread from Northeast Greenland to Svalbard, Franz Josef Land and Novaya Zemlya. Svalbard and Franz Josef Land are a key region for this population, although the majority stays in the east, in the Russian Arctic. There is an interesting sexual segregation: The bulls tend to stay in Spitsbergen, while the cows together with their calves obviously prefer the northeasternmost parts of Svalbard and Franz Josef Land. In recent years, sightings of females and calves have increased also in Spitsbergen. This very positive tendency is due to the general return of Walrus to their original range pre-dating the arrival of Europeans in Spitsbergen, who introduced hunting that almost led to regional extinction of Walrus in Spitsbergen in the 1950s. Even today, most Walrus in Svalbard are found in the northeastern parts of the archipelago, which was not visited by early whalers. One well-known colony is at the southern tip of Moffen.

Walruses hauled out on shore on Amsterdamøya.

Walrus spend the whole year in the same region, but move away from the coast and towards open water during the winter. They need polynyas: areas that remain ice-free during the whole winter due to currents. Polynyas occur on the northern sides of both Svalbard and Franz Josef Land. As soon as the coast becomes ice-free, walruses return to their traditional haul-out sites. They tend to use the same sites year after year: beaches near shallow, productive waters with muddy bottom, where they find good feeding grounds. After a successful feeding trip, they may rest for several days ashore – up to eleven days of siesta have been observed (who has observed this for eleven days?), and in historical reports there is talk about Walrus sleeping on the beach for about seven weeks!

During the little ice age, there were occasional sightings of Walrus in the River Thames, and in the early 20th century, a Walrus even got lost in the southern Baltic sea.

Biology: The preferred diet consists almost exclusively of the mussel Bluntgaper (Mya arenaria), which lives in the mud at the sea bottom and filters plancton. Walrus can sense the mussels with their whiskers and use their nose, and possibly a strong jet of water that they produce to uncover the mussel. Then they will suck the meat out of the shells. The stomachs of Walruses have been found to contain up to 70 kg of mussel meat, but not a single shell! Productive and shallow waters are obviously an important part of their habitat.

Bluntgaper (Mya arenaria), the preferred diet of walrusses in Svalbard. Several thousand years old specimens in glacio-isostatically uplifted marine sediment (raised beaches) on Nordaustland.

There are single individuals that have a different taste and predate on seals. These Walrus have got a particularly high level of contamination with environmental toxins (heavy metals, PBCs etc.).

Mating is between December and February and copulation takes place in the water near the ice edge. Bulls have heavy fights for females, during which serious injuries occur. A single calf is born 15 months later, in May of the following year. The female will separate from the herd to give birth on an ice floe. The calf spends about two years with its mother.

Walrus family life: cow with calf. Near Edgeøya.

Miscellaneous: The size of the Walrus population in Svalbard and Franz Josef Land is estimated to be between 3,000 and 4,000 animals and is increasing. The strong skin, that was used amongst other things for machine belts during the early days of industrialisation, and also the ivory were highly sought-after goods. Since the 17th century, there has been heavy hunting pressure on Walrus in Spitsbergen. On countless occasions, several hundred animals were killed within hours. Before those cruel days, Walrus must have been very abundant anywhere in Svalbard, even including Bjørnøya.

Hunting was finally banned completely in 1952, and this total protection is still in force in Svalbard. The population is increasing, but still nowhere near its original size. Recent threats include disturbance at the haul-out sites, contamination with environmental toxins, climate change and oil spills.

Polar bears occasionally try to kill a Walrus, although they have respect for the strong tusks. Orcas may be dangerous for Walrus in the water. Other than that, there is no predator that Walrus would have to fear. Little is known about the life expectancy, but it will surely be beyond 30 years, possibly 40.

Walrus are easily disturbed ashore. Anybody who approaches Walrus that are hauled out on the beach, has to exercise the greatest care: Slow approach, no noise, no sudden movements, no smell being blown towards the Walrus and, especially, a respectful distance are key factors to avoid disturbance. 30 metres should definitely be the minimum distance for any approach (this is also the distance set by AECO guidelines), and in many cases you will have to stay further away, depending on the animals and the situation. Let them know you are there at an early stage; this is definitely better than them finding out about your presence when you are already close. The worst case scenario is a whole herd leaving a resting place in panic, all rushing into the water. For reasonable photos, you need a telephoto lens, but 300 mm should normally do.

There is no indication of disturbance by visitors being a problem for walrus.

Curious walrus at Prins Karls Forland.

Next to the view, it is the sound that can be quite impressive; just imagine up to 70 kg of raw mussel meat being digested in every stomach! Considering this, it is not surprising that also the smell can leave you with unforgettable impressions.

On shore, Walruses are rather klutzy and slow, but in the water, they are very much in their element and accordingly agile and fast. Bear this in mind when you have them nearby small boats. Often, Walruses are rather peaceful animals, but their curiousity may reach unpleasant degrees and aggression including attacks on small boats and even yachts is not unheard of.

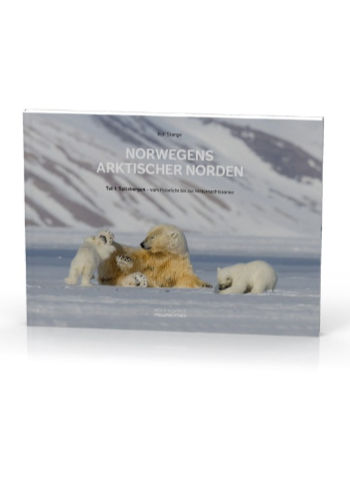

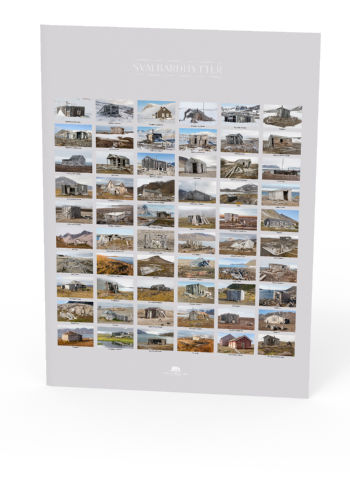

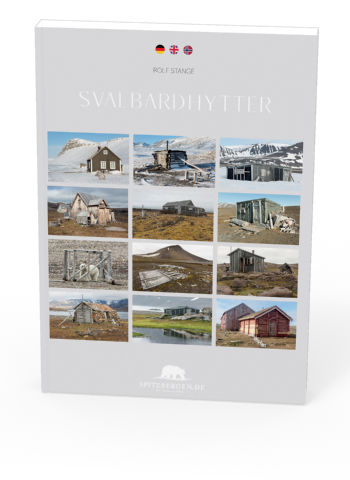

BOOKS, CALENDAR, POSTCARDS AND MORE

This and other publishing products of the Spitsbergen publishing house in the Spitsbergen-Shop.

last modification: 2019-03-16 ·

copyright: Rolf Stange