-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

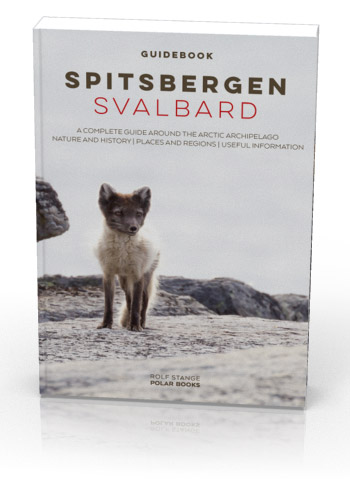

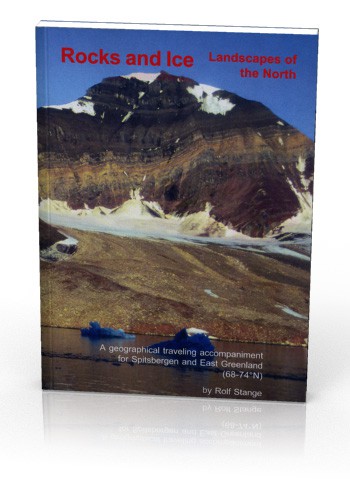

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Page Structure

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

-

Newsletter

| Guidebook: Spitsbergen-Svalbard |

Svalbard reindeer (Rangifer tarandus platyrhynchus)

Svalbard reindeer (bull). Blomstrandhalvøya, mid September.

Description: The Svalbard reindeer (or Spitsbergen reindeer) is the only reindeer species in Svalbard. It is a unique, relatively small subspecies. Both sexes have antlers, but those of the males are bigger. Male reindeer grow their antlers from April to July, shed the bast in August and September and finally the antlers in late autumn, after the breeding season. Females get their antlers in June and carry them until spring next year.

Females: Weight 53 kg in spring, 70 kg in autumn. Length 1.50 metres.

Males: Weight 65 kg in spring, 90 kg in autumn. Length 1.60 metres.

Svalbard reindeer: cow and calf. Alkhornet, early August.

In contrast to Scandinavia where semi-wild reindeer stay together in large herds, you will see either single animals or small groups in Svalbard. Herds of more than 20 animals are exceptional. Svalbard reindeer are not domesticated and do not belong to anybody.

Svalbard reindeer: strong male. Hornsund, late August.

Distribution / Migration: Reindeer occur everywhere in the Arctic, but the subspecies “Svalbard reindeer” is endemic to Svalbard. They were driven near to extinction in the early 20th century due to extensive hunting, but have recovered well and can now be found in most parts of the archipelago, although man has helped on some occasions by moving small stocks within Spitsbergen to suitable areas. There are even some reindeer chewing on the very meagre vegetation in the polar deserts on Nordaustland, but they do not occur on the remotest islands of Storøya, Kvitøya, Hopen and Bjørnøya. Highest population densities occur in areas with rich tundra vegetation, mainly Nordenskiöld Land and the large islands of Edgeøya and Barentsøya. Within these areas, they do not show a very pronounced seasonal migration pattern, as winter and summer feeding grounds are within the same regions. Reindeer walk across fjord ice and glaciers to move around.

During the late spring in 2011, about 1000 reindeer were counted in Adventdalen, which gives an average density of about 6 animals per square kilometre, three times more than in Finnmark (north Norway). Continuous counting started in 1979 in this area, and the average from the beginning to 1995 was 650 animals. The recent increase is explained with the changing climate by the the responsible biologist, Nicholas Tyler.

Svalbard reindeer on barren winter tundra. Sassendalen, mid April.

Biology: Svalbard reindeer will eat almost anything that has roots and leaves, with a few exceptions such as Arctic bell-heather (Cassiope tetragona). During the summer, they spend most of the time feeding to accumulate a thick layer of fat, which is their main energy source for the winter when food availability is low. Reindeer spend the winter in places where the snow has been blown away by the wind, to have access to some vegetation, often at some altitude. Late winter and spring are the most difficult time of the year, when the tundra is still hidden under snow and their fat reserves are used up. Especially when periods of thaw are followed by frost and everything is covered with an impenetrable layer of hard ice, reindeer are faced with difficult times. Starvation during such periods and when the teeth are worn down after about ten years are the main causes of death. Few reindeer die during the rich summer season. Mating is in October.

During this time, strong bulls will defend a harem of up to ten cows. During the following early summer, around June, a single calf will be born. The proportion of females that give birth varies strongly from ten percent in difficult years up to 90 percent in good times. There are accordingly very pronounced fluctuations of the population size.

Miscellaneous: The size of the total population is estimated to be around 10,000 animals, thereof about 4,000 in Nordenskiöld Land, but varies from year to year. Reindeer have been protected in Svalbard since 1925, but limited hunting has been introduced for locals in 1983 in designated areas in Nordenskiöld Land. The hunting season is in September and it is assumed that hunting does not affect the population. In 2006, 296 permits were issued, but only 178 reindeer were shot.

Tourists and reindeer in Kongsfjord.

Despite hunting, reindeer can be very curious and sometimes approach groups of tourists to a distance of within ten metres. They spend most of the day walking slowly over the tundra, feeding permanently, and do not pay any attention to humans to begin with. Then, they are typically undecided between running away and coming closer. Snow mobiles can pose serious strain on reindeer during the most difficult season, when they need to save energy. Pay attention to this and give reindeer the right of way. During the summer, you will often find reindeer hair on the tundra. Wishful thinking suggests that this is Polar bear fur, but the distinction is easy: Reindeer fur is much coarser, but breaks easily, whereas the finer Polar bear hairs are much thinner and stronger.

Reindeer in Longyearbyen, mid April.

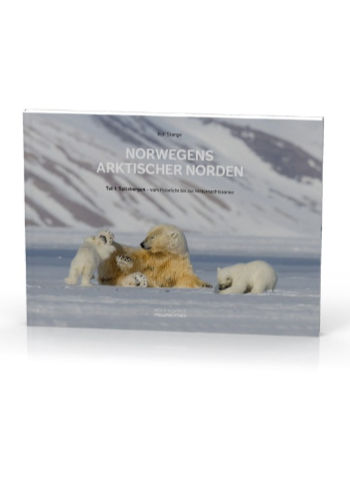

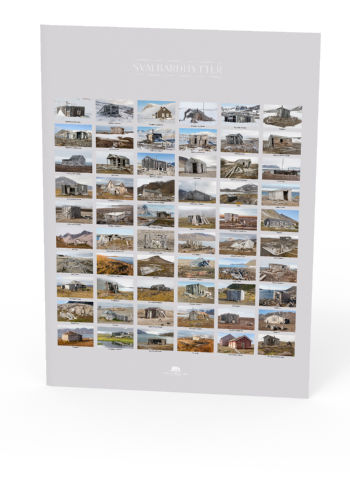

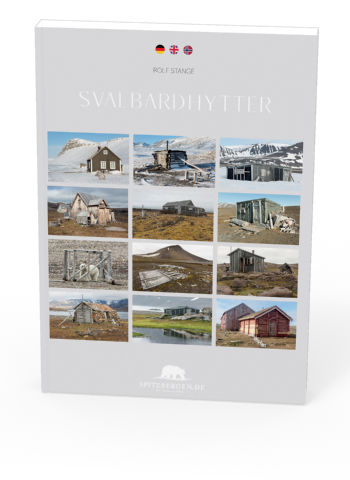

BOOKS, CALENDAR, POSTCARDS AND MORE

This and other publishing products of the Spitsbergen publishing house in the Spitsbergen-Shop.

last modification: 2019-03-14 ·

copyright: Rolf Stange