-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

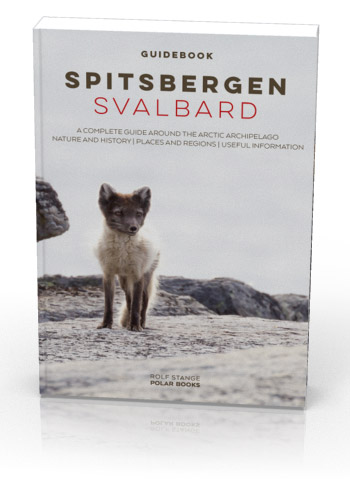

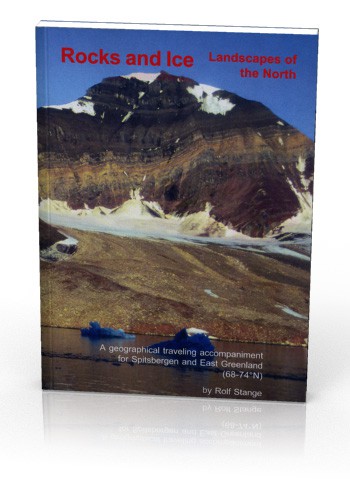

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Page Structure

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

-

Newsletter

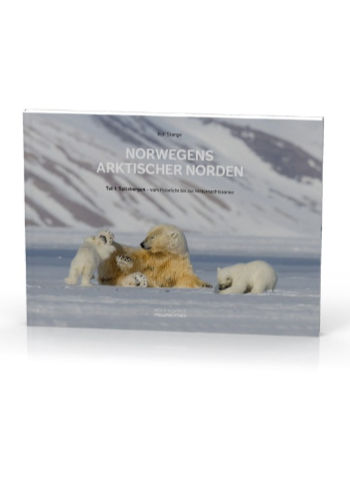

| Guidebook: Spitsbergen-Svalbard |

The race to the pole 3: Ny-Ålesund

History of Spitsbergen - Amundsen and Nobile

Roald Amundsen 1904

After Wellman, it remained calm again for a couple of years regarding attempts to reach the pole from Svalbard.

The Zeppelin-expedition, 1910

In the meantime, the expedition of the German count Zeppelin showed in 1910, that improved airships might indeed be useful in the arctic, although they didn’t have a ‘Zeppelin’ (commonly used for ‘airship’ in German), ‘just’ the count with the same name. They sailed mostly in the Kongsfjord and Krossfjord with their ship, the large cruise ship Mainz, and a smaller expedition ship that could also enter smaller bays. Prince Heinrich of Prussia, brother of emperor Wilhelm II., was one of the expedition members.

Roald Amundsen

Roald Amundsen was still busy with his Maud-expedition in the northeast passage, but he left the Maud when it he got a bit bored in the end – too much science, too few adventures. He rather focussed on reaching the pole by air, as more advanced aircraft became available. The north pole had been his great dream for the whole of his life. He chose Ny-Ålesund as a base for his expeditions, as this was located quite close to the pole, it was easy to reach by ship and the workers of the coal mine could assist him, which meant that he could do with reduced own labour force, which made the financial side much easier.

Roald Amundsen’s 1925 North Pole expedition

For his first attempt, Amundsen brought two Dornier-Wal-Seaplanes, N-24 and N-25. They started on 21st May 1925 and did not return, so everybody thought they were lost for good. After a crash landing on the pack ice near 88°N, Amundsen and his five men first had to build a runway in the uneven ice to enable one of the two aircrafts to take off again. Norwegian pilot Riiser-Larsen accomplished a masterpiece when he started the one remaining aircraft with two crews on board (six men altogether) from the short runway on the ice. Lack of fuel forced them to land again near the northern coast of Nordaustland, where a Norwegian sealing ship picked the expedition up and brought them back to Ny-Ålesund.

Amundsen – Ellsworth – Nobile expedition, 1926: the airship Norge

Amundsen did not hesitate and started a second attempt in 1926. After the experience of 1925, he wanted to try an airship this time. Italian Umberto Nobile constructed the airship Norge for Amundsen and navigated it up to Spitsbergen. While the Norwegians together with Nobile and Amundsen’s American sponsor Lincoln Ellsworth were still busy with preparations, the American Richard Byrd showed up with his Fokker-aircraft Josephine Ford. Byrd started 09th May 1926 and came back 15 hours later, claiming that he had reached the pole. Nowadays, most historians agree that Byrd can not have reached 90°N, but Amundsen could not know that. He started a few days later with Nobile and Lincoln Ellsworth as well as an Italian crew on board the Norge. The flew across the pole, dropped their countries national flaggs and reached Alaska without difficulty. The most dramatic part of this expedition came later, when Amundsen and Nobile, the young nation of Norway and fascist Italy, fought over the honour.

Nobile, 1928: the Italia-catastrophe

The result was that Nobile tried once more in 1928 to show everybody that they could do it without Norwegian contribution. The result is one of the most well-known dramas in the history of the north pole. The Pole was reached, but the Italia crashed on the pack ice north of Nordaustland on the way back, somewhere near the little island of Foynøya. A part of the airship disappeared together with 6 men who were never to be seen again. 9 men landed on the ice, amongst them Nobile, who was seriously injured during the crash.

During the following weeks more than 20 aircraft and 14 ships from 6 different nations tried to find the lost expedition. Amongst them was Amundsen, who took off on 18 June in Tromsø with the French seaplane Latham. Latham disappeared with her crew including Amundsen, she probably crashed somewhere near Bjørnøya (Bear Island). After a while, Nobile’s radio operator managed to send an SOS with their position. Subsequently, Swedish pilot Ejnar Lundborg managed to land on the ice near Nobile’s camp and evacuated the most seriously injured man: Umberto Nobile, together with his little dog Titina (this did not make a good public impression). Unfortunately, Lundborg crashed his plane on the second attempt to land and he was then stuck together with the remaining Italians. All were later picked up by the Sovjet icebreaker Krassin (Lundborg was actually picked up by another Swedish plane shortly before the Krassin arrived).

In the meantime, a party of three men had tried to walk over the ice without getting very far; one of them, the Swede Malmgren (meteorologist and the only non-Italian crew member of the Italia) disappeared under uncertain circumstances, the two Italians who were with him were also rescued by the Krassin.

Members of the 1926 trans-polar flight in Seattle: Riiser-Larsen, Amundsen, Ellsworth, Nobile (and his dog)

With the 1926 flight, both poles had definitely been reached, at least by air, and it was clear that no major islands remained to be discovered in the arctic. This was thus the end of the heroic age of arctic exploration, which focussed on reaching even higher latitudes and spectacular discoveries. Gradually, the »heroic age« gave way to systematic science.

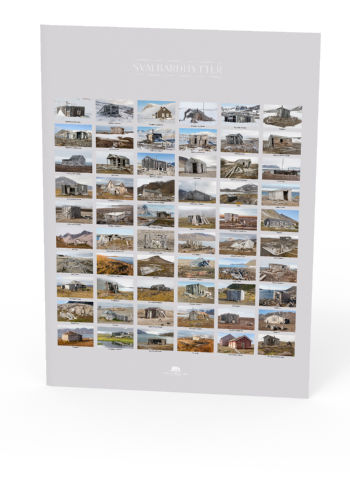

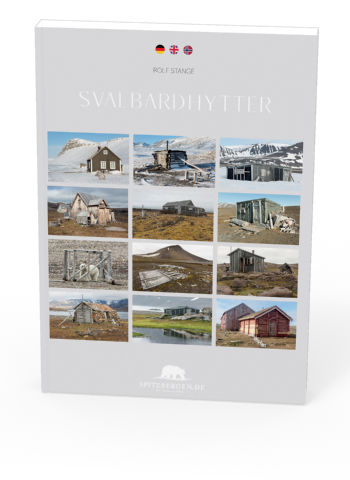

BOOKS, CALENDAR, POSTCARDS AND MORE

This and other publishing products of the Spitsbergen publishing house in the Spitsbergen-Shop.

last modification: 2019-04-14 ·

copyright: Rolf Stange