-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

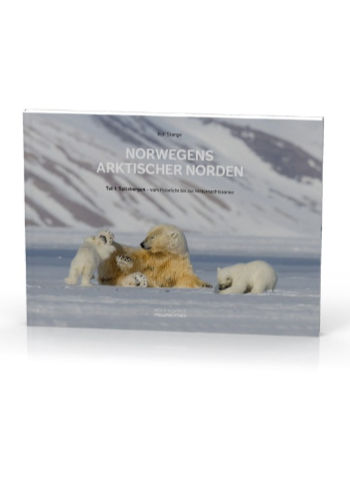

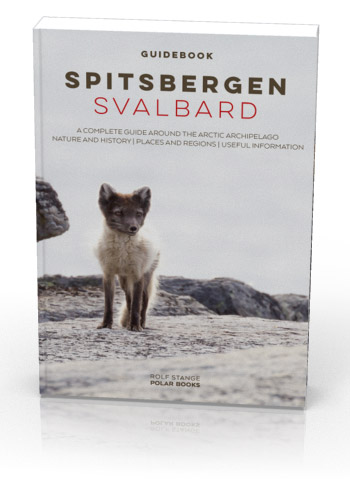

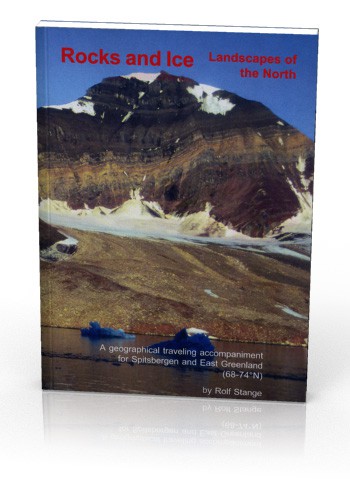

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Page Structure

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

-

Newsletter

| Guidebook: Spitsbergen-Svalbard |

Home

→ Spitsbergen information

→ Islands: Spitsbergen & Co.

→ Isfjord

→ Yoldiabukta: Wahlenbergbreen, Sveabreen

Yoldiabukta: Wahlenbergbreen and Sveabreen

Glacier landscape in northern Isfjord

Yoldiabukta is a bay on the north side of Isfjord.

The geography in this part of Isfjord is a bit confusing: Nordfjord is a huge branch of Isfjord, located on the north side and itself branching out again several times. On the west side is Yoldiabukta, between Bohemanflya in the south and Mediumfjellet in the north. The Wahlenbergbreen glacier reaches the shore in Yoldiabukta.

North of Yoldiabukta is another, smaller bay between Mediumfjellet and the flat land of Sveasletta. This bay also has a glacier, Sveabreen. However, the bay itself has no name, which is probably due to the fact that it has only recently been formed by the retreat of Sveabreen.

Sveabreen in atmospheric September light.

Strictly speaking, Ekmanfjord and Dicksonfjord, further north, are also part of Nordfjord. To cut a long story short: Here we are looking at Yoldiabukta and its northern neighbour bay with Sveabreen. Everything else (Ekmanfjord, Dicksonfjord) has its place elsewhere.

View from Muslingodden towards “Nordre Yoldiabukta” and Sveabreen.

It is practical to have a name for the bay with Sveabreen, so here we will refer to this bay as “Nordre Yoldiabukta”, northern Yoldia Bay. Makes sense, doesn’it? And while we are at it, we can collectively refer to Yoldiabukta proper and its northern neighbour as “Yoldia Bays”. I think that will just make things a bit easier.

View from Muslingodden towards “Southern Yoldiabukta” and Wahlenbergbreen.

By the way, the Yoldiabukta got its name from the mussel Yoldia arctica, which is now officially called Portlandica arctica. A post-glacial predecessor of the Baltic Sea was also named after this mussel: the brackish Yoldia Sea, which existed 8000 years ago and in which this mussel was common.

Geology

Geology is one of the areas in which the Yoldia bays can shine. To start with, it is about the fact that sedimentary rocks from the end of the Palaeozoic and the beginning of the Mesozoic can be found here, because this transition between the great ages of evolution (which is what these ages are more about than the actual history of the Earth) is exciting. After all, this transition was one of the greatest global mass extinction events of all time, probably the result of unimaginably large volcanic eruptions that flooded millions of square kilometres of land with molten lava. However, this did not happen in Svalbard, but in other parts of the world. This global catastrophe marked the end of the ancient period in the history of life and the beginning of the Mesozoic period in the history of life: the dinosaurs arrived.

The last phase of the end of the Palaeozoic was the Permian, followed by the Triassic at the beginning of the Mesozoic. This great extinction is therefore known as the Permian-Triassic boundary. Finding a place in the area where the rocks document the end of the world at that time (which is exactly what it was from the point of view of many species) sends a shiver down the spine of anyone interested in geology! And this is exactly what you can experience in the Yoldia bays, especially in the northern one, in Lappdalen west of Sveasletta. The hills and mountains to the west of the valley are made up of older limestone from the Permian period (Kapp Starostin formation, known from Tempelfjord, Akseløya in Bellsund, Ahlstrandhalvøya in Van Keulenfjord, etc.). In Lappdalen itself, the bedrock is Triassic. There must be some dinosaur bones somewhere! Elsewhere in Isfjord, bones of marine dinosaurs, such as plesiosaurs and pliosaurs, have been found in exactly these layers. They can now be seen in museums in Longyearbyen, Tromsø and Oslo. And if you don’t find a dinosaur, there’s a good chance you will find an ammonite or a shell impression.

Think of all the treasures you could find in these mountains:

fossil corals, brachiopods, ammonite and clam impressions and even dinosaur bones!

But you need to take your time to discover their secrets.

For the sake of completeness, it should be mentioned that the Upper Permian is missing in Svalbard. These layers may never have been deposited, or they may have been eroded away later. It is like a book from which someone has torn out a few pages. That is bad, because part of the history is missing. You have to live with it. That’s why geologists work all over the world: they look for the missing part of the story somewhere else, you will always find it somewhere in the end.

But what will probably catch the eye of people with less geological knowledge are the fantastic structures: Svalbard was pushed and pressed from the west as Greenland began to break away. Both islands used to form one large landmass. Or to put it better: North America and northern Europe together formed a huge northern continent. The North Atlantic did not exist at that time. As it formed, the coasts of the resulting ocean were first squeezed and folded on both sides. This led to the formation of the beautiful fold patterns on the west coast of Spitsbergen, which here extend as far east as Yoldia Bays. The deformation does not continue murch further to the east: Ekmanfjord is tectonically much less disturbed, with far fewer folds and faults in the mountain sides.

Geological structures on the east side of Mediumfjellet at Sveabreen.

Mediumfjellet between Wahlenbergbreen and Sveabreen is particularly well known among geologists in the area for its wildly beautiful structures, but the other mountains, especially on the west side of Wahlenbergbreen, are not inferior.

I actually thought this section would be a short three-liner 😄 but it didn’t work out. Never mind.

Landscape

Rugged mountains with wild geological structures, two fairly active glaciers, moraine covered shorelines, extensive plains in the outer areas of the shores (Bohemanflya in the south, Sveasletta in the north). That’s the short version.

Moraine landscape on the shore of Sveasletta, view towards Sveabreen.

The glaciers have retreated several kilometres since the ‘Little Ice Age’ in the 18th century. The large moraine landscapes on the shores on all sides of the Yoldia bays are evidence of this. In the recent past, however, both Wahlenbergbreen and the Sveabreen have occasionally advanced.

Glacier edge of the advancing Wahlenbergbreen (2017).

This behaviour is called ‘surge’, more about this can be found on the Borebukta page, as Borebreen showed the same behaviour around 2023-2024.

Coastal landscape at Stavneset.

This combination of wild mountains and active glaciers, which sometimes leave a lot of ice floating on the water, is a big part of the scenic charm of the Yoldia Bays.

Coastal landscape at Sveabreen.

And when you look on the map at the wide plains of Bohemanflya in the south or the smaller plains of Sveasletta, including neighbouring Lappdalen, you’ll feel like going hiking!

Aber meist sind es die Gletscher mit ihren oft aktiven Abbruchkanten und den in der Bucht treibenden Gletschereisstücken, die zuerst ins Auge fallen und die Aufmerksamkeit und die Objektive auf sich ziehen.

Drifting glacier ice near Sveabreen.

Flora and fauna

There is not much to see in the Yoldia bays themselves. Of course, you can always find a bearded seal, a ringed seal or the odd walrus on the ice. Sometimes a herd of belugas wanders through the bay, and occasionally a polar bear wanders along the shore.

Polar bear in northern Yoldiabukta.

But there are no permanent highlights, such as a large bird cliff, and the vegetation on the young moraines along the shore is sparse.

Purple saxifrage at Wahlenbergbreen.

The long, ice-free stretches of Bohemanflya and Sveasletta are a different matter: here you will find vast areas of tundra with dense vegetation, which in summer can become a colourful carpet of flowers, and of course reindeer and other typical tundra animals roam the land.

History

We can keep this section really brief: there hasn’t been much going on here. On the north side of Bohemanflya and on the north side of Muslingodden (the headland east of Mediumfjellet) there is a small trapper’s hut built by Harald Soleim in the 1970s. And that’s about it for this area.

Photo gallery: Yoldiabukta & Wahlenbergbreen

Some impressions of the beautiful landscape: mountains, glaciers, ice. The first six pictures are from 2006, when Wahlenbergbreen looked very different from what it looked like during its advance around 2017 and afterwards. That’s why these old pictures are included, even though you can see that back then digital cameras hadn’t developed too much from woodcuts and engravings.

- gallery anchor link: #gallery_3529

Click on thumbnail to open an enlarged version of the specific photo.

Photo gallery: Northern Yoldiabukta & Sveabreen

Separate for better overview: the bay north of Mediumfjellet (‘northern Yoldiabukta’) with Sveabreen.

- gallery anchor link: #gallery_3526

Click on thumbnail to open an enlarged version of the specific photo.

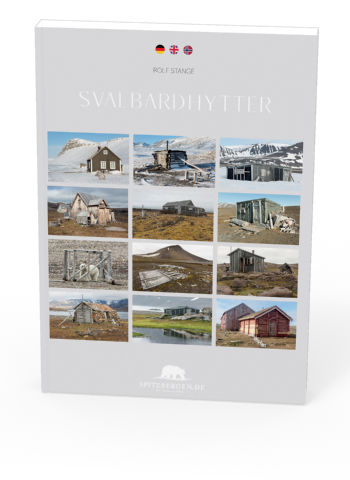

BOOKS, CALENDAR, POSTCARDS AND MORE

This and other publishing products of the Spitsbergen publishing house in the Spitsbergen-Shop.

last modification: 2025-02-12 ·

copyright: Rolf Stange