-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Page Structure

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

-

Newsletter

| Guidebook: Spitsbergen-Svalbard |

Home → December, 2024

Monthly Archives: December 2024 − News & Stories

A little Christmas present: new Spitsbergen pages

P.S. TLDR? Too long, don’t feel like reading, rather get straight to the point? At the bottom of the post are the links to the new pages: Akseløya, Midterhukhamna and the old mines on the north side of Adventfjord.

The last few weeks have once again been jam-packed, but it was worth it, working on the new edition of the Spitsbergen guidebook. More on this in a few weeks from now.

Polar night atmosphere in Adventdalen.

The picture shows the illuminated corner station of the old coal-fired cable car at Endalen.

At the same time, I have been working on a couple of pages dedicated to certain areas and individual locations on Spitsbergen. After all, that’s where you can travel online, getting to fantastic places with just a mouseclick which otherwise are difficult to reach, if at all.

Hint of a northern light over Longyearbyen.

These include, among others, four pages that together illustrate the largest more or less contiguous monument of industrial history in Spitsbergen, namely the mining landscape from the early 20th century on the north side of Adventfjord:

- Advent City was the first ever attempt on Spitsbergen to mine coal industrially.

- Hiorthhamn followed a few years later and is one of Svalbard’s most remarkable cultural monuments from the pioneering days of coal mining with its shoreline complex.

- Sneheim is the old mine belonging to Hiorthhamn. At an altitude of 582 metres on Hiorthfjellet, incredible!

- The old mess and accommodation area “Ørneredet” is part of the Sneheim mine, the old mine belonging to Hiorthhamn.

Also new are the pages about Russeltvedtodden (ever heard of that?) at the southern end of Akseløya (ah of course … the beautiful Akseløya in Bellsund) and Midterhukhamna. And there are brand new pages dedicated to Sassenfjord respectively Tempelfjord. Oh yes, don’t forget a quick trip to Agardhbukta on the east coast 🙂

The moon above the old cable car centre in Longyearbyen.

Climate change in Svalbard’s fjords and the Arctic Ocean

A few weeks ago, I wrote about Record melting of Svalbard’s glaciers in 2024, on this site, focussing on consequences of climate change on land.

But of course the changes are not limited to the land; the sea is also affected. Or, perhaps more accurately, it plays a major, driving role.

The Gulf Stream

In the North Atlantic, much is known to depend on the Gulf Stream. With its comparatively warm water masses, it brings enormous amounts of heat from the south and thus ensures the relatively mild climate in the highest latitudes such as 78 degrees north, where the Isfjord today remains largely ice-free all year round, while some fjords in northernmost Greenland or Canada (Ellesmere Island) only become ice-free briefly in summer or not at all.

Even small changes in the Gulf Stream have a massive impact on the regional climate in the north-east Atlantic. If the Gulf Stream brings a little more warm water or if the water is a little warmer, the North Atlantic will become considerably warmer. If the supply of warm water decreases or no longer reaches as far north, a regional cooling could also occur that could affect the whole of north-west Europe. In the long term, this scenario cannot be ruled out as part of climate change, but the opposite is currently the case.

Kongsfjord

Jørgen Berge from the University of Tromsø has been keeping a close eye on Kongsfjord for more than 20 years. As the research settlement of Ny-Ålesund is located in Kongsfjord, this fjord has been studied closely for a long time, with decades of data available on all kinds of details. In addition, the fjord is located on the part of the west coast that is most strongly influenced by the Gulf Stream, so it can serve as an early warning system for changes in these currents and their local effects.

Kongsfjord near Ny-Ålesund: an oceanographic and marine biology research laboratory.

Berge told Barentsobserver about his work and observations. The result anticipated: a ‘radical change in the marine ecosystem.’

According to Berge, the water masses in the Kongsfjord are warming by 0.1 degrees per year across the entire water column, i.e. by no less than 2 degrees in just 20 years. Two degrees is quite enough to drastically change the oceanographic-ecological character of a sea area – and the warming does not stop. The character of the Kongsfjord has changed from ‘arctic’ to ‘Atlantic’ during this time. In oceanographic terms, this initially means that the water is warmer and saltier.

The ecosystem: plankton and seabirds

Of course, this is not without consequences for the ecosystem. High-arctic, fat-rich plankton such as the copepod Calanus glacialis is increasingly being displaced by its subarctic and less fat-rich relatives Calanus finnmarchicus and Calanus hyperboreus, which has consequences for seabirds that feed on plankton. The high Arctic Little auks in particular, which used to be – and still are, as of now – very numerous, prefer to feed on the energy-rich Calanus glacialis. If they have to rely more and more on their less energy-rich relatives, their diet will become increasingly problematic.

Little auks on the west coast of Spitsbergen.

Recent history shows that the breeding populations of seabirds are shrinking almost everywhere in the North Atlantic. The little auks still seem to be doing quite well, but it is very difficult to count these very small birds that breed invisibly under rocks. The case is clear for guillemots, puffins and gulls, where some colonies in northern Norway have practically collapsed since the 1980s. Disappeared.

Fjord ice: ringed seals and harbour seals

Another aspect is that the Kongsfjord has hardly frozen over for around 15 years. Ringed seals, once the most numerous seals in the fjords of Spitsbergen, need the fjord ice in spring to give birth to their young and to rest. The harbour seal, which is also known from the southern North Sea, is now much more common on the west coast of Svalbard than the ringed seal, which is very similar in appearance. Seals have been naturally occurring in Svalbard for thousands of years and this observation may be coincidental, but it fits in with the scientifically confirmed development of the fjords from a highly arctic ecosystem to an Atlantic one.

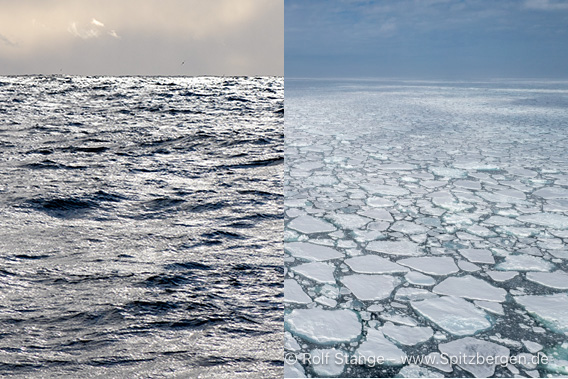

High Arctic ringed seal (left), subarctic harbour seal.

Both live on the west coast of Spitsbergen.

Fish, mussels and temperature records

Berge also speaks of a change in the species composition of fish and mussels. Species such as herring and capelin, which one would not expect to find in high Arctic fjords, are spreading, as are mussels.

More and more common in Svalbard: blue mussels.

Global warming is more noticeable at the poles than at lower latitudes; it is estimated that the Arctic is warming by a factor of three to four more than other regions. If one hopes that climate change can somehow still be limited to a warming of 1.5-2 degrees, then this figure is the global average. For the Arctic, you can multiply that by three or four.

In recent years, record temperatures have been regularly measured in Svalbard, most recently on 11 August at 20.3 degrees, the highest value ever measured on an August day near Longyearbyen.

Even the previously high Arctic fjords in the north-east of Svalbard will not remain unaffected by this development. This is confirmed both by a regular look at the ice map and by personal experience in the fjords of Nordaustland and in Hinlopen Strait, where the previously widespread water temperatures of around 0 degrees are now rather rare and small-scale, especially in the southern Hinlopen Strait and on the southern side of Nordaustland, where the cold East Spitsbergen Current from the Arctic Basin is still exerting its influence. In the northern Hinlopen Strait and in the fjords in the west and north of Nordaustland and up to Sjuøyane, water temperatures of 6-8 degrees are increasingly common, indicating the increasing influence of mild Atlantic water (Gulf Stream).

Rarely ice-free in the past, now regularly in summer:

Fjords on the north coast of Nordaustland.

The Arctic Ocean: from white to blue

The sea ice of the Arctic Ocean is both a victim and a driver of this development. This is one of those feedback effects in the global climate system where the effect reinforces the cause. In this case, an area of water that has become ice-free due to warming no longer reflects the sun’s rays, but absorbs them and converts them into heat, which in turn melts even more ice and even larger areas of water absorb the sun’s rays … and so it goes on.

According to a study recently published in Nature Communications, the Arctic Ocean could become ice-free on a daily basis by around 2030. This study is the first to look at the development on a daily rather than a monthly basis. The Arctic Ocean could therefore be ice-free on a daily basis in a few years’ time if warm winters with little ice formation are followed by warm early summers with high ice loss.

The Arctic Ocean of the future: increasingly blue instead of white.

On the other hand, the study also describes scenarios according to which an ice-free Arctic Ocean will not be observed by the year 2100. Both possibilities are rather extreme scenarios; the real development may lie somewhere in between. Or not, the extreme scenarios are also possible according to the scientific models.

As Jørgen Berge told Barentsobserver: ‘It is likely that the central Arctic Ocean will evolve from a white (ice-covered) ocean to a blue (open water) ocean. What that means, we don’t know.’

Calendar “Spitsbergen & Greenland 2025”: the stories behind the photos

A while ago, I started telling the stories of the pictures in the new photo book ‘Spitsbergen – Cold Beauty’, and I wanted to continue that. Now it is about the new calendar, but the idea is the same: the stories behind the photos, as I’m finally getting round to picking it up again.

The 2025 calendar is a double calendar, Spitsbergen and Greenland are presented with 12 pictures each. Here we have November and December, so four pictures and four stories in total.

Calender “Spitsbergen & Greenland 2025”: November

Autumn in the Arctic – during this time of year, we are hoping for beautiful light. Low sun during daytime and endless sunsets. Of course, the sun doesn’t shine at all in Svalbard in November, as the polar night begins at the end of October. The Spitsbergen picture for the November page was taken on a beautiful day at the end of August 2022, on the first ever circumnavigation of Spitsbergen with sailing ship Meander. The weather was really on our side, and then you can go to crazy places where you wouldn’t normally go. Because they are very exposed, because the waters close to the shore are uncharted and shallow.

This is exactly the case in the extensive Diskobukt on Edgeøya. Here, every wave quickly turns into a breaker even before it reaches the shore, and at low tide the propeller whirls in the mud well before you get anywhere near the coast. It is sensible to stay away from such places in everyday life. But not every day is everyday life, and we are not always sensible, are we 😄 otherwise where would we end up … certainly not in this part of Diskobukta! (This is not about the relatively well known kittiwake colony in the northern part of Diskobukta.) Where we were ashore in the evening of this unforgettable day and went for a little hike to and up a low hill. I had seen this hill so many times from a distance as we sailed past and always thought that one day I would have to go there … and this was just the right opportunity! It just has to happen, you can’t force things like that.

Diskobukta on Edgeøya (not the one in west Greenland) is aptly described as ‘vast’ or ‘wide open’. Barren, high arctic, a vast, darkly coloured alluvial plain. Numerous whale bones add variety to the otherwise monotonous landscape impression, and the great light of a beautiful evening at the end of August at around 78 degrees north did its part.

The November-Spitsbergen-image shows Diskobukta on Edgeøya.

I had been there years before. On that occasion: horizontal snow – and a polar bear on the shore. That was great too. But that evening at the end of August, when we were able to go ashore … unforgettable! That’s the stuff my Spitsbergen dreams are made of. It was so beautiful that I realised on the spot that one of the pictures would be in the calendar as soon as possible. ‘Calendar potential’ is the highest photographic standard here 🙂

The other stories are told relatively quickly. In Scoresbysund in East Greenland, the musk ox is roughly what the polar bear is to Spitsbergen: tourists usually want to see them.

Now they usually stand somewhere far away on a mountain slope. It takes a bit of luck to see them up close. And too close is also potentially unhealthy, of course, especially when you are hiking.

One fine day with early winter mood in September in Rypefjord, deep in Scoresbysund, everything was just right: the musk oxen were quite close to the shore and we could see them perfectly well from the boat – the lovely Ópal from Iceland. And very helpful to secure not only some nice views, but actually good photos: I had my 600 millimetre lens with me, the really big one that usually stays in Spitsbergen and lives on the ship rather than being dragged around on land. Just for the polar bears. Or in Greenland for the musk oxen. The effort was worth it here.

The November-picture for Greenland: Musk oxen in Rypefjord.

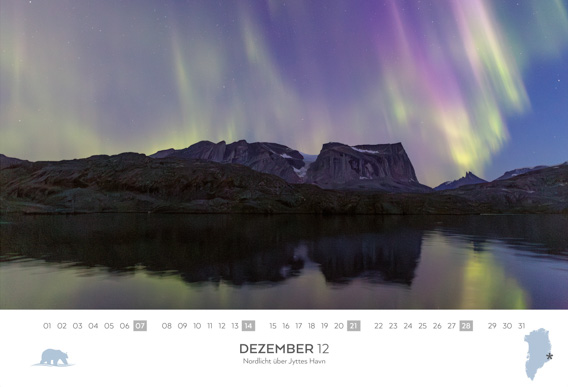

Calender “Spitsbergen & Greenland 2025”: December

Of course, I wouldn’t miss the northern lights at the end of the year. December is the deepest polar night, and of course, you just can’t get to the most remote corners of Spitsbergen at this time of year. But why should you, you can see the northern lights wonderfully in Adventdalen, not far from Longyearbyen.

The December-image, Spitsbergen: Northern light above Adventdalen.

Large parts of Greenland, including Scoresbysund, are actually even better for observing the northern lights than Svalbard, where you are already north of the hot aurora zone, the Aurora Oval. Scoresbysund is the right place to be, as there is a lot of action when it only gets dark at night. And due to the more southerly location, this is the case earlier in the year than in Svalbard, September is a pretty reliable month. In this picture we see the northern lights over Bjørneøerne, with the magnificent Øfjord and the striking Grundtvigskirke mountain in the background.

The December-picture, Greenland: northern light over Bjørneøerne.

The double calendar ‘Spitsbergen & Greenland 2025’ is available in the Spitzbergen.de webshop in two sizes (A3 and A5), as well as many other great things – not just books – of course.

Advent season in Longyearbyen

Now, Longyearbyen is located in Adventfjord, isn’t it 🤪😵💫 this is actually not only one of my infamous puns, but actually a not so rare misunderstanding. The name Adventfjord has nothing to do with the Advent season, but with an English whaling ship, the Adventure, which was there in the 17th century.

But that’s not what this is all about, it’s about the start of the Advent season in Longyearbyen. There is also a Christmas market here, or rather two, even. However, they are a little different to what most of us may be used to. On two weekends, in mid-November and last weekend, the hard-working and creative artists, craftspeople and everyone in between set up their stalls, first in the cultural centre (Kulturhuset) in the town centre and on the first weekend of Advent in the artists’ centre (kunstnersentrum) in Nybyen higher up in the valley, where the gallery used to be some years ago. Unfortunately no roasted almonds and no mulled wine, but lots of great handicrafts made in Longyearbyen, including Eva Grøndal from the local photographer dynasty of the same name (first picture) and Wolfgang Hübner-Zach from the carpentry workshop Alt i 3 (that’s where the beautiful kitchen boards and driftwood picture frames come from 😉). And lots of other great things. Lena’s deceptively real chocolate fossils, awesome! To name just one more example.

Christmas market in Nybyen

- gallery anchor link: #gallery_3402

Click on thumbnail to open an enlarged version of the specific photo.

And then, of course, there is the traditional torchlight procession on the afternoon of the first Sunday in Advent – it is dark, even the street lights are switched off in the area during the event – from the Huset to Santa’s letterbox below the old pit 2b, the ‘julenissegruve’ (Santa’s pit). Father Christmas is working hard up there now, so this old coal mine, abandoned since 1964, is now lit up again until Christmas. And down by the road is the letterbox where the children (including the older ones, if they want to) post their letters to Father Christmas with all their wishes.

The route continues to the centre, where the Christmas tree is lit. Of course, there are warm words, cheerful singing and good cheer and, last but not least, Father Christmas arrives with his assistants and distributes a small advance to the many children.

The Christmas tree is lit

- gallery anchor link: #gallery_3405

Click on thumbnail to open an enlarged version of the specific photo.

This marks the start of the Advent season in Longyearbyen, and everywhere else too, of course. I wish everyone a happy and joyful Advent season!

News-Listing live generated at 2025/April/30 at 21:37:06 Uhr (GMT+1)