-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

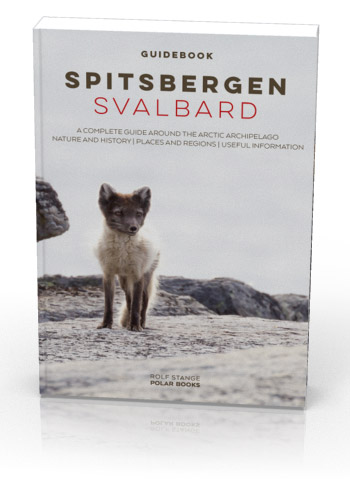

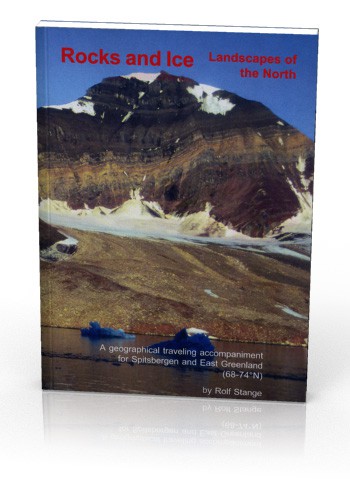

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Page Structure

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

-

Newsletter

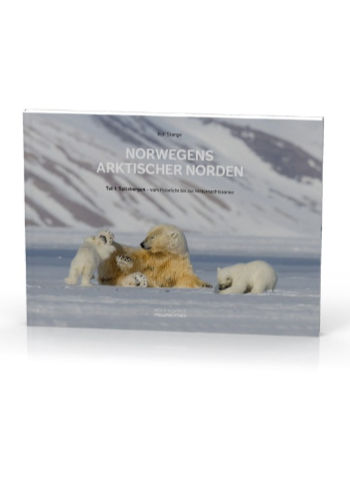

| Guidebook: Spitsbergen-Svalbard |

The early years of Barentsburg, Colesbukta/Grumant and Pyramiden

Barentsburg (2009). Russian companies have been mining coal here (including Heerodden/”Kapp Heer”) since 1932, interrupted only from 1941 to 1946 by the war.

The historical roots of Russian coal mining in Spitsbergen, however, go back to 1912.

Next to the Norwegians, the Russians are the only ones who have been active with coal mining throughout most of the 20th century and until today. Surprisingly little knowledge is publically available, however, about the early history of Barentsburg, Colesbukta, Grumantbyen and Pyramiden.

On this site I want to make an attempt to summarize the beginning of Russian mining in Spitsbergen briefly. These early activities were the base for today’s Russian settlements, Barentsburg and Pyramiden, as well as Colesbukta and Grumant. The latter two ones should be considered one double settlement rather than two functionally independent ones. Colesbukta and Grumant were abandoned in the late 1960s. There are individual pages with information and photos (mostly panoramic) for all of these places.

Mine entrance or ventilation shaft near Barentsburg.

Coal and other mineral occurrences of economical interest were found in Spitsbergen in the late 19th century mainly by Swedish geologists. Word soon spread to Russia, where the demand for energy for the evolving northen coast and was growing. The area did not have any resources in terms of primary energy and long distance overland transport was expensive and troublesome (obviously, nothing was known about oil and gas on the Russian continental shelf in the Arctic back then). Another issue was the Russian navy fleet in the Baltic Sea, which was dependent on English coal – not at all a desireable situation from a Russian perspective. Altogether, there was a solid base for the Russian interest for an independent source for coal somewhere north.

Rusanov and Samoilowitsch

Merchants in Arkhangelsk equipped an expedition to the Arctic led by Vladimir Alexandrovitsj Rusanov in 1912. Amongst the members was a mining engineer named Rudolf Lasarewitsch Samoilowitsch. Samoilowitsch was later to become a leading arctic explorer and geologist in Russian. His activities led to the foundation of the Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute in St. Petersburg in 1920. His role reminds of Adolf Hoel in Norwegian arctic circles at the same time.

Rudolf Lasarewitsch Samoilowitsch (1883-1939?).

Unknown photographer, common license. Black and white image, artificially coloured.

In 1937, Samoilowitsch was involved in a large expedition with several ships in the Russian arctic. The ships got unexpectedly stuck in ice and had to winter. This included the large icebreakers Sadko, Malygin and Sedow as well as a number of smaller ships. Samoilowitsch got the blame for the unfortunate development. Upon his return, he was arrested and he was murdered under arrest in 1939 or 1940.

The Russian Expedition to Spitsbergen in 1912

Back to the expedition to Spitsbergen in 1912. The scientists were supposed to map coal occurrences, to secure promising coal fields and to get an overview of already ongoing mining activities. Additionally, general research in classical fields such as botany, zoology and hydrography was to be carried out as much as possible.

The expedition had 14 members. They left Alexandrovsk on the Kola Peninsula on 26 June 1912 on the engine-driven cutter Herkules. During the next weeks, the north side of Van Mijenfjord was investigated. Rusanov and two sailers made an overland expedition from there to the coast of Storfjord on the east side of Spitsbergen to investigate this area. Then, the expedition went to several areas in Isfjord, including Green Harbour (Grønfjord), Adventfjord, Skansbukta and Colesbukta. Claims were made on a narrow, north-south trending stripe of land between Colesbukta and Van Mijenfjord, and later, an area in Trygghamna and further west as well as the west side of Borebukta followed. Then, the expedition went on to do some work on Prins Karls Forland, in Kongsfjord and in Krossfjord.

The expedition finished field work in Spitsbergen on 18 August. Samoilowitsch and two other members returned to Norway on a Norwegian steamer. Rusanov and the others went on with the Herkules to continue in the northeast passage. There, the whole expedition disappeared. Rusanov, ten more men and the ship – all gone, never to be seen again, and with them, all results of their work in Spitsbergen other than those that Samoilowitsch had taken with him.

Vladimir Rusanov (1875-1913?).

Unknown photographer, common license. Black and white image, artificially coloured.

Samoilowitsch saw coal mining potential in four different areas and made claims to all of them: the north side of Van Mijenfjord, Spitsbergen’s east coast between Kvalvågen and Agardhbukta, the Isfjord coast between Colesbukta and Adventfjord and Borebukta on the north side of Isfjord. Further claims were made in Engelskbukta, Skansbukta and Rindersbukta angemeldet.

“Modern” (from 1970) signpost marking Russian claims on Bohemanflya.

On 16 March 1913, the Arkhangels merchants behind the 1912 expedition founded the company Grumant – A.g. Agafeloff & Co, to which the claims in Spitsbergen were assigned.

The second expedition (1913)

Preparations for coal mining began in 1913 with an expedition with 25 men on two ships led by Samoilowitsch. The ships were the Maria (600 tons, Arkhangelsk) and the smaller Norwegian cutter Grumant. Samoilowitsch decided to establish a base on the east side of Colesbukta, where workers went ashore to start preparations for mining. Two houses were built, one for accommodation and one for storage, including the hut at Rusanovodden.

Colesbukta, where the Russian expeditions until 1915 had their base.

It turned out that the coal seam that had attracted the attention of Samoilowitsch was below sea level in Colesbukta, but another seam was found 60 m above the sea in “the second little valley east of Colesbukta”, namely Grumantdalen. Investigations were made there, during which 4 tons of coal samples were extracted.

While these works were going on, a rather unfriendly meeting took place between the Russians and the Americans from the Arctic Coal Company (ACC) in Longyear City (today Longyearbyen). John Munro Longyear himself and his deputy Scott Turner, a person not known to be afraid of entering conflicts, called Samoilowitsch a liar and laid down protest verbally and in writing as they considered the Russian activities an infringement of their own rights. In the end, the american protests got bogged down in international diplomacy and they finally came to nothing.

Grumant (today known as Grumantbyen).

Here, the Russian expedition of 1912 found promising coal occurrences.

The Russian expedition left Spitsbergen in early September. Two men stayed behind to guard the Russian property in Colesbukta (Rusanovodden) during the winter. The wintering did, however, not go well: one of the men got scurvy. Far too late, they went to Longyear City for help. Despite medical treatment, the sick man died one day after their arrival, and the other one lost several toes and fingers due to heavy frostbite. He stayed with the Americans for several months.

The expeditions in 1914 and 1915

Investigations were continued in Colesbukta and Grumant in 1914 and 1915, but no further details are known about these expeditions. It seems that the work was done by two men led by Samoilowitsch. These expeditions were the last ones from Russia for a while, because the first world war started in 1914 and the 1917 revolution in Russia.

The development after the first world war until 1932

The first world war did not touch Spitsbergen directly. But it did have implications of local importance, as several companies including the Russian Grumant – A.g. Agafeloff & Co withdraw from Spitsbergen. After the war, the price increase for coal on the world market led to a phase of renewed activity in coal mining also in Spitsbergen in the early 1920s.

Old mine entrance on Bohemanflya.

But not much happened on the Russian side for a while. Green Harbour/Barentsburg and Rijpsburg (Bohemanneset/Bohemanflya) were founded and developed by the Dutch NeSpiCo (Nederlandsche Spitsbergen Compagnie). In Grumant, the Anglo Russian Grumant (ARG) established mining activities and a Swedish company started in Pyramiden.

There are individual pages dedicated to each of these places:

In 1931, the Russian mining installations and claims were taken over by the state-owned Trust Arktikugol. Briefly, a company named Sojusljesprom surfaced as a temporary owner, but this company does not appeared to have been a real player in this context. From 1932 and until today, the Trust Arktikugol owns and operates the Russian settlements and properties in Spitsbergen. Refer to the pages linked above for the further history of the invidual places.

Sources

Good sources for the Russian settlements and associated mining and other history in Spitsbergen is scarce, to put it mildly. Once I was pleased to finally find a newly published book about the Russian history of Spitsbergen – just to realise quickly that it was a Russian translation of the Norwegian standard book Svalbards Historie by Thor Bjørn Arlov. This is a modern standard textbook, but one of its shortcomings is exactly the focus on the Norwegian perspective and a lack of material on the Russian side (of course there is some information about the Russians included, but it leaves a lot to be desired in this respect).

It is amazing that a Norwegian book was translated into Russian instead of the publication of an original Russian work. It is hard to believe there there is no dedicated historian in Russian arctic circles, which are strong and active, both capable of and motivated and in a position to compile a history of Spitsbergen (Grumant) from a Russian perspective. This would be the Spitsbergen book that is still missing, and I still hope that it will be written and published one day. This would be something for a historian with good language skills, good contacts in political, scientific and mining circles and access to relevant archives. Or is that asking for too much?

As long as such a book does not exist, we will have to make do with Adolf Hoel’s Svalbards historie 1596-1965. Which is an amazing piece of work with a great wealth of information, so we should be glad to have it, but – please, anyone with relevant skills and abilities, just go ahead … 🙂

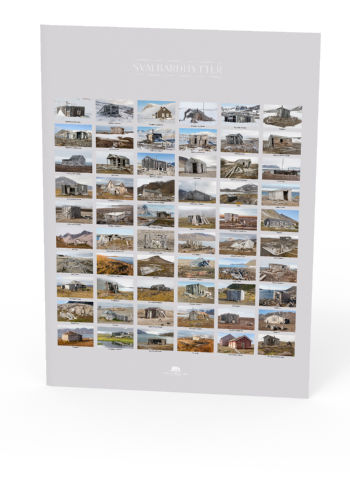

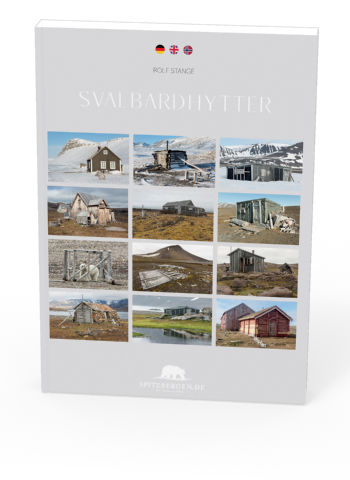

BOOKS, CALENDAR, POSTCARDS AND MORE

This and other publishing products of the Spitsbergen publishing house in the Spitsbergen-Shop.

last modification: 2020-12-20 ·

copyright: Rolf Stange