-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

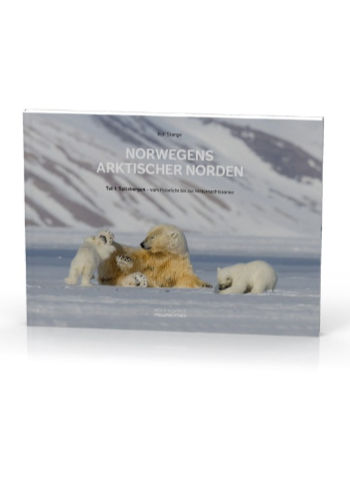

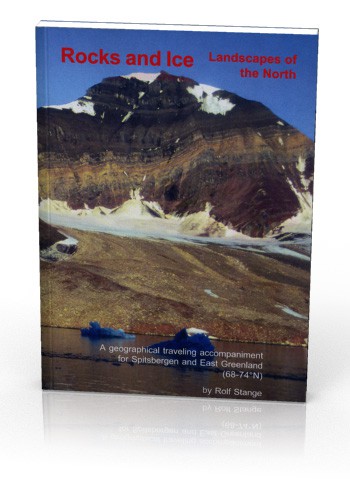

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Page Structure

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

-

Newsletter

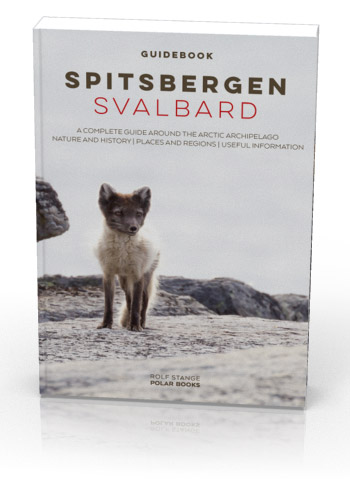

| Guidebook: Spitsbergen-Svalbard |

Home

→ Spitsbergen information

→ Islands: Spitsbergen & Co.

→ Spitsbergen (Northern part)

→ Woodfjord

Woodfjord

Natur and history of a fjord in northern Spitsbergen

Woodfjord is a large fjord on the north coast of Spitsbergens.

There are two branches on its western side: Liefdefjord and Bockfjord.

General

Woodfjord is a large fjord on the north coast of Spitsbergens. It is a actually a fjord system with several branches: Liefdefjord and Bockfjord are also part of the Woodfjord-area.

The west side of Woodfjord is part of the Northwest Spitsbergen National park, the island groups in the entrance to Liefdefjord are bird reserves (see Liefdefjord). The east side of Woodfjord is not a specially protected area, but the Svalbard environmental law is valid there just as everywhere.

View from north to south over the outer part of Woodfjord (Gråhuken).

Woodfjord cuts with several slight bends 60 km from north to south into the island of Spitsbergen. There are no major branches other than the two fjords on the west side mentioned above and there are only a few smaller bays. Some small capes structure the coastline and there are no islands (Stasjonsøyane and Måkeøyane are part of Liefdefjord, even though this may be a bit of geographical hair-splitting). Compared to other fjords that are more strongly structured by bays, peninsulas and islands, Woodfjord is a bit of a long tube.

View from south to north over inner Woodfjord.

The hydrology and geomorphology of the fjord itself is quite special: Woodfjord is almost everywhere pretty deep, 60-100 metres in the inner part and in the outer part, north of Bocksfjord and Verdahlspynten, more than a 100 metres. Even close to the shore it is so deep that it can be difficult to find suitable anchor depths (at least for smaller ships which prefer to drop anchor on 5-20 metres of water). It is usually either too deep or too shallow to drop anchor, there is mostly not much in between!

And when the wind is blowing in a north-south direction (or the other way around), then Woodfjord can be something of a wind channel with very strong funnelled winds. But on a good summer day, the landscape with its red slopes and green tundra can be almost painfully beautiful and it can appear to be kind of almost mellow and soft, at least compared to the rugged, steep mountains and huge glaciers in its western neighbour Liefdefjord. Woodfjord does not have any such landscape features, no glaciers anywhere near the shore. Andrée-Land between Woodfjord and Wijdefjord further east is indeed one of the least glaciated parts of Spitsbergen.

Woodfjord panorama

There are several pages on this website dedicated to individual sites in Woodfjord, with photo galleries, more background information and 360-degree panorama images:

- Velkomstpynten the northeast point of Reinsdyrflya, with a ruin of a hut built by the famous trapper Stockholm-Sven.

- Gråhuken in the north, where Christiane Ritter wintered (“A woman in the polar night”, see history section further down on this page.

- Mushamna, a famous trapper hut.

- Wigdehlpynten, a little peninsula with typical landscape features of inner Woodfjord.

Geology

The geology of the region dictates the landscape and it can really be an eye-catcher. This makes it worthwhile spending some thoughts on it, something that does not require any previous knowledge, just some interest in the matter. So let’s go ahead 🙂

You can also read the relevant section on the Liefdefjord page. The geology in Woodfjord is simpler than in Liefdefjord. In Woodfjord, the geological basement is not exposed at the surface, in strong contrast to Liefdefjord.

One term is enough to describe the geological building material of Woodfjord: Old Red. In (kind of) short words: the Old Red is a thick pile of sediment layers deposited near 400 million years ago. Shortly before that (well, in geological terms), collision of tectonic plates had created a huge mountain chain: the Caledonian mountains. Just as any mountain area rising above its surroundings, the Caledonian mountains where exposed to erosion as soon as uplift had started, and the eroded sediment was transported to and deposited in the surroundings lowlands. As these lowlands were subsiding at the same time, thick sediment piles could accumulate, with thicknesses reaching 10 kilometres and more.

In the early stages of this process, when the Caledonian mountains had just been uplifted so that the landscape featured huge differences in altitude within a short horizontal distance, the deposited sediment tended to be of coarse grain size and not well sorted: we are talking about breccias and conglomerates, often deposited in steep, torrential rivers, as slope sediment or alluvial fan: typical sedimentary environments on the fringes of any high mountain area.

Later, the difference in altitude became less pronounced and sedimentation accordingly calmer, more fine-grained and better sorted. Typical results include siltstone, often deposited as mud in wide lakes and lagoons, and even well-sorted dune sands, to mention two examples. At times, the lowlands were even covered by shallow sea.

Fossil finds are rather rare in Woodfjord. Imprint of a shell at Gråhuken.

In the warm and semi-arid climate of that time, chemical weathering produced large amounts of hematite, an iron oxide with a distinct reddish colour. Hematite, is, however, not present in the whole sediment pile. The red layers that gave the Old Red its name (the second half, that is) form the older (structurally lower) part of the whole pile. The time when these sediments were deposited was the Devonian.

Woodfjord: an Old Red landshape.

It is nothing you can take for granted that a sediment pile survives a period of time as long as almost 400 million years. It certainly helped that the sedimentation area subsided so that the accumulating sediment was protected from erosion (in contrast to uplifted areas = mountains which are exposed to erosion). Subsidence happened along faults (huge cracks). The resulting structure is a graben. This particular case is amongst geologists known as Andrée Land graben, after the land area of Spitsbergen between Woodfjord and Wijdefjord further east.

The red layers of the Old Red can be found many in inner Woodfjord. Further north, the rocks are grey rather than anything else (placename “Gråhuken” = Grey Hook). In the south, the mountains are red. A beautiful colour and a stunning landscape experience on a day with good weather and light!

Grey section of the Old Red (“Grey Hook formation”), Mushamna.

On the west side of Woodfjord, on Reinsdyrflya, you have the red layers of the Old Red also in the northern section of the fjord

Now we have covered about 99 % of the geology of Woodfjord. For those with some special interest it should be mentioned in addition that there was volcanic activity in the area during the Neogene (comment: younger Tertiary, as it was known before, but the term “Tertiary” is officially not in use anymore). In the Miocene, to be more precise, about 15 million years ago. Lava streams filled the shallow valleys of the landscape back then. This landscape was later strongly eroded. Then, the lava streams turned out to be more resistent to erosion then the surrounding Old Red. As a result, the former valleys, then filled with lava streams, now form some of the highest peaks in central Andrée Land – valleys were turned into mountain tops! This is called inverted relief by geomorphologists. You can see some remnants of those lava streams with columnar structures on mountain tops east of inner Woodfjord (east side).

Foreground: Devonian Old Red. Upper slopes in the background: Miocene lava flows.

Verdalspynten area.

There was more volcanism during the Quaternary (“ice age”). This is now evident especially in neighbouring Bockfjord, where there is an eroded volcanic ruin and some warm springs (don’t expect too much, they don’t compare to their relatives in Iceland and elsewhere). In Woodfjord, there is an eroded volcanic plug now known as Halvdanpiggen. It is a rock column standing out from a slope 800 metres high as a geological detail mentioned here for curiousity and the sake of completeness.

Halvdanpiggen (mid right), an eroded volcanic plug.

Landscape

The large-scale landscape features are directly linked to the geology and the local climate. A fact that will quickly catch the attention of any curious visitor is the absence of glaciers near sea level in Woodfjord. In contrast, there is a couple of large, ice-free valleys, something that otherwise is pretty rare in most parts of Spitsbergen.

Verdalen, a large unglaciated valley in Andrée Land.

The northern part of Woodfjord, especially at Gråhuken and Reinsdyrflya, is surrounded by large coastal plains covered by series of fossil beach ridges due to postglacial isostatic land uplift.

Coastal plain with fossil beach ridges at Gråhuken.

Lowland areas are considerably smaller in inner Woodfjord and mostly restricted to some capes and some valleys with valley bottoms filled by braided rivers. Other than that, the mountain slopes are mostly coming close to the shore. Compared, for example, to inner Liefdefjord or the northwest corner of Spitsbergen, the mountains are less steep and jagged, with more rounded slopes. Another example of the geology taking control of the landscape, in co-operation with climate.

Lowland at Verdalspynten.

There are some special features here and there locally. The most well-known one is certainly the lagoon of Mushamna, which is separated from the fjord by a long, narrow spit that leaves just a narrow entrance to the lagoon itself which is one of Spitsbergen’s best sheltered and most beautiful anchorages for smaller vessels that can get in there.

Entrance into the lagoon of Mushamna.

For those with some special interest in geomorphology, there is a pingo in Verdalen, although it is certainly not Spitsbergen’s most spectacular specimen of this large permafrost phenomenon. But it is, at least, one of rather few pingos more or less close to the coast.

In innermost Woodfjord, glacial retreat has left a huge moraine landscape and the lake Jäderinvatnet with a huge meltwater river from the lake to the fjord. The red colours of this landcsape, on a good summer day with blue sky, are stunningly beautiful! Author’s opinion, that is 🙂

Flora and fauna

Polar bears roaming around anywhere in Woodfjord are certainly not rare, and reindeer can be found anywhere, although not in great density. But all in all, wildlife is not what makes Woodfjord stand out: there are no walrus colonies (you may of course meet the odd walrus or two resting on a beach anywhere) and no spectacular seabird colonies. But the northern part of Woodfjord, especially the entrance area, has a reputation for being an area that is regularly frequented by whales, including large finn and blue whales.

Blue whale in outer Woodfjord.

The lowland areas are to varying degrees covered by tundra. In the north, around Gråhuken, the coastal plain is very barren and polar-desert-like. There is more vegetation on the west side, on Reinsdyrflya.

Steppe vegetation in inner Woodfjord.

Further in the fjord both the vegetation and often also the soil surface make it pretty clear that the local climate is dry. Species like the mountain avens are common, and desiccation cracks and mineral precipitation can be seen many places, giving evidence of precipitation being exceeded by evaporation

Desiccation cracks, Wigdehlpynten.

History

It is said that there is a graveyard from the time of the early whalers on Reinsdyrflya, somewhere near Mullerneset. Other than that, there are no traces from those early years in Woodfjord – but some (Norwegianised) placenames including Mushamna (“Mouse harbour”) and Velkomstpynten (“Welcome point”). Pomors have certainly used the area, such as in Mushamna, where faint remains of a Pomor hunting station can be seen near the lagoon (on its north or rather northwest side).

Trappers in the “Norwegian period” of trapping used the Woodfjord field, which included Liefdefjord, often in the early 20th century. Especially the 1920s were a busy period, when Hilmar Nøis and other members of his adventurous family from Andøya (Vesterålen) built cabins such as the one in Mushamna (the old one near the shore), Vårfluesjøen (“Fiskebay”), Gråhuken, Worsleyneset (“Villa Oxford”) and others.

Old trapper hut (built in 1927). A real “Nøis-hut” (see text).

Next to Mushamna, the hut at Gråhuken is certainly the most famous hut in Woodfjord and beyond. This is where Christiane Ritter wintered together with her husband and Norwegian Karl Nikolaisen in 1934-35, an adventure that later resulted in the now famous book “A woman in the polar night”.

The Gråhuken hut was used for winterings also in later years, and there are actually two more published books of winterings at Gråhuken: “Vinterland. Glimt fra ei arktisk dagbok” (Bjarne Nordnes and Åsa Johansson, 1975) and “Gråhuken. Fangst og ferie på 80 grader nord” (Marit Karlsen Brandal, 2017, from a wintering in 1982-83).

The famous trapper hut at Gråhuken.

In 1987, the Norwegian adventurer and trapper Kjell Reidar Hovelsrud built his beautiful hut at Mushamna, which he later sold to the Sysselmester who used to lend it to interested people for winterings to keep the tradition alive for a while, but this has not been done anymore for some years. Too much effort, as they say … well, anyway. Read more about the history of the huts and trappers in Woodfjord by clicking on the linked names of the huts in the text above. There is a book (actually several ones) by Kjell Reidar Hovelsrud about his arctic adventures. Good read! If you read Norwegian, that is.

The hut built in 1987 by Kjell Reidar Hovelsrud. It is now owned by the Sysselmester.

Photo gallery – Woodfjord

A wild mixture of impressions from Woodfjord, from Gråhuken in the north to the innermost part of the fjord. Landscapes, wildlife, huts, …

- gallery anchor link: #gallery_2949

Click on thumbnail to open an enlarged version of the specific photo.

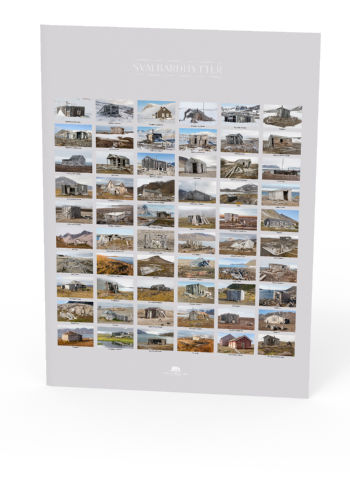

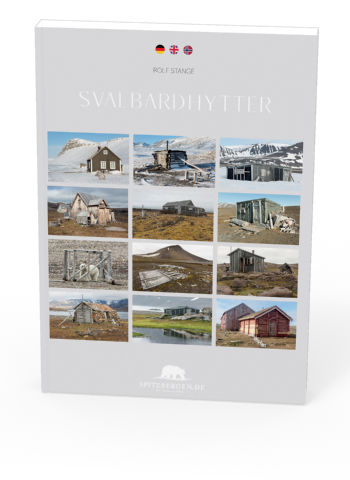

BOOKS, CALENDAR, POSTCARDS AND MORE

This and other publishing products of the Spitsbergen publishing house in the Spitsbergen-Shop.

last modification: 2023-11-18 ·

copyright: Rolf Stange