-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

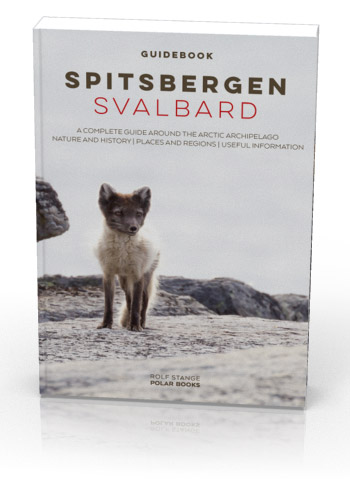

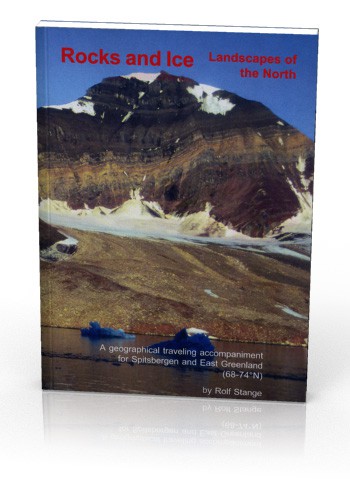

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Page Structure

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

-

Newsletter

| Guidebook: Spitsbergen-Svalbard |

Home → * News and Stories → The future energy of the Arctic

The future energy of the Arctic

And again, it is about energy, far from the first time on these pages. It is an important debate in Longyearbyen, has been so for a while and this won’t change at any time soon.

Last autumn, Longyearbyen’s old and outdated coal power plant was finally shut down and replaced with diesel generators which now supply the approximately 2,500 inhabitants, companies and infrastructure with electricity and long-distance heating.

Diesel is not exactly a sustainable and environmentally friendly solution, neither is it cheap. The high costs are currently a matter of hot debate; plans of the community council to let the four largest energy consumers carry all the extra costs are not met with great enthusiasm as one might expect. If the price increase, as it is currently calculated, is to be paid for by all consumers, then the energy prices might well triple. In 2023, the price for prive households (up to 10,000 kWh per year) was 2,42 kroner (ca. 0.21 Euro) – plus an annual basic fee of 2883 kroner (255 Euro).

It is feared that tripling the price may well force companies to close and population to leave.

Part of the technical challenge is that, in contrast to “normal” places, it is not possible to link Longyearbyen’s energy infrastructure to a larger regional network. It is not possible to use anything that already exists in the area, because Longyearbyen is completely isolated and far away from the rest of the world.

But this is a challenge that Longyearbyen shares with hundreds of other small places all over the Arctic. Good reason for doing research about possible solutions to find out what the future energy of the Arctic might look like.

Isfjord Radio at Kapp Linné: former station for coastal radio and communication,

now wilderness hotel and laboratory for energy solutions in isolated places.

Such research is being done at Kapp Linné, the location of the old radio station Isfjord Radio. The radio and other communication infrastructure are not in use anymore since Svalbard is connected to mainland Norway with a glass fibre cable. But the buildings have been used for a wilderness hotel since the late 1990s. The owner of the place is the Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani (short Store Norske or SNSK), mostly known as the Norwegian coal mining company that ran the mines in Longyearbyen (still operative) and Sveagruva (closed). The hotel is run by Basecamp Spitsbergen.

The place has several characteristics that make it suitable as a laboratory to test energy solutions: it is very small with with only a small handfull of people as a “permament” population, and even when hotel capacities are fully used the population increases to only a few dozen people. There are no other consumers.

The point is not to develop completely new technology, but to establish systems where the components are all based on existing technology which in itself is tried and tested. Central control and battery systems are considered essential. In a first phase, a photovoltaic system installed in 2023 stands for a large part of the energy requirement. This may surprise in an area that does not get any sunlight at all for about 4 months per year. But the hotel is closed during the dark period, and then, a block of batteries and a heat storage tank can buffer at least some of the variations. Diesel generators take care of the rest, but this is already enough to reduce the diesel consumption by 70 %, as Store Norske told Svalbardposten.

In the next phase, wind power is expected to increase the fraction of renewable energies in the total mix to 90 %, but this is still matter of negotiations with authorities. There are legal obstacles as Isfjord Radio is a protected cultural heritage site and there is a bird sanctuary right next to it.

An energy supply of 100 % renewables is, with current knowledge and technology, not possible. This would require a regional energy network that does not exist. In fully isolated places, a backup of diesel generators will be required to guarantee energy supply at any time, but these at some stage may be run with biofuels or hydrogene. But this is currently merely a dream of the future. On the other hand, a diesel reduction of 70 % with the prospect of a further reduction to 90 % appears as a good success.

The idea is to use the knowledge thus established elsewhere, in Longyearbyen and other places in the Arctic. Longyearbyen already has a couple of smaller photovoltaic systems, the largest one so far is at the airport.

And other places are also interested: despite the political ice age, the Russians in Barentsburg have already contacted the community in Longyearbyen and expressed the desire to establish a dialogue to exchange knowledge about sustainable local energy solutions, a desire generally met with benevolence in Longyearbyen.

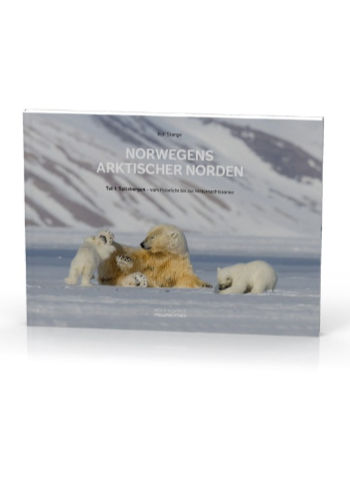

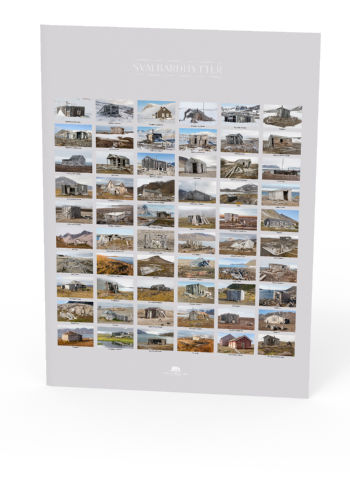

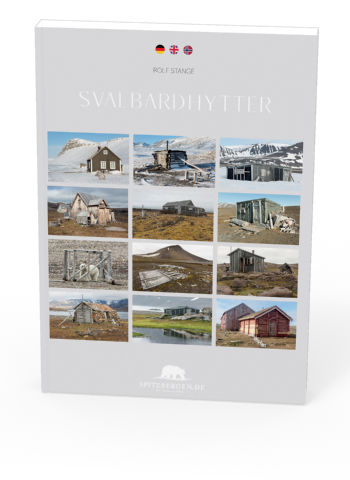

BOOKS, CALENDAR, POSTCARDS AND MORE

This and other publishing products of the Spitsbergen publishing house in the Spitsbergen-Shop.

last modification: 2024-01-18 ·

copyright: Rolf Stange