-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

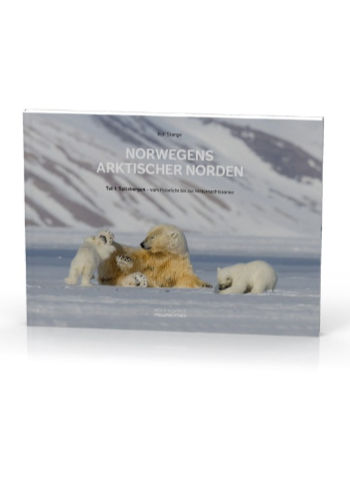

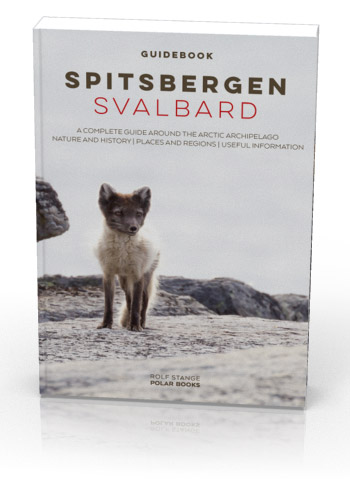

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Page Structure

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

-

Newsletter

| Guidebook: Spitsbergen-Svalbard |

Home → * News and Stories → Norwegian government dispossesses foreigners of local voting rights

Norwegian government dispossesses foreigners of local voting rights

After a long and controversial political process, the Norwegian government in Oslo has now made the decision that non-Norwegian inhabitants of Longyearbyen will lose the voting right (active and passive) on a community level. Only those “foreigners” (people without Norwegian passports) who have lived at least 3 years in a mainland community will be able to vote or to be elected into the community council (Longyearbyen Lokalstyre).

This applies to approximately 700 inhabitants of Longyearbyen. There is currently one member of Lokalstyre who has a passport other than Norwegian (Olivia Ericson from Sweden), according to NRK.

This had been a very controversial and, for some, emotional debate which was already subject of several earlier contributions on this page; read the previous article (click here) for more background, e.g. on the history of local democracy in Longyearbyen.

It is safe to assume that most non-Norwegian citizens have not spent 3 years as a registered inhabitant of a Norwegian mainland community. Many locals who have spent a major part of their lives in Longyearbyen will not be allowed to vote during the next local elections (in 2023) and they may not be elected into Lokalstyre.

The recent governmental decision frustrates many who are concerned; many feel like second-class citizens now, as Svalbardposten reports.

Minister of justice Emilie Enger Mehl gives the following explanatory statement (quoted from the press release of the Norwegian government, link above, my own translation): “The connection to the mainland makes sure that those who manage the community at any time have good knowledge and a good understanding of Svalbard politics and the (political) framework that is applied to Svalbard … considerable resources are transferred every year from the mainland to support public services and infrastructure. Inhabitants with mainland connection will often have contributed to these finances. The requirement for a mainland connection is also to be seen in this light.”

Longyearbyen is becoming more Norwegian. Exclusion of non-Norwegian inhabitants from local democracy is a price that the Norwegian government is appearently willing to pay.

Comment

So far so clear: those who (potentially) have paid are to decide; those who have paid potentially less (local taxes are low) and to not have the right passport are excluded from political participation where it really matters.

Longyearbyen Lokalstyre is a community council and no more than that. Lokalstyre’s decisions concern local traffic, kindergarten, school, other local infrastructure – just what a community council generally does, and no more than that. Lokalstyre does not have any influence in national legislation – beyond trying to be heard, which too often does not happen, otherwise the decision in question would not have happened as it did. Lokalstyre does not make decisions concerning Svalbard outside the community of Longyearbyen.

So one may ask what kind of problem the Norwegian government assumes to solve. Or, same question in other words: what are they afraid of? So far, Longyearbyen Lokalstyre is firmly in Norwegian hands. There is currently exactly one local council member who is not Norwegian, and that is Olivia Ericson from Sweden. Who is afraid of Olivia? And even if, one future day, Danes and Swedes, Germans and Thai would make up a visible proportion of Longyearbyen Lokalstyre and thus have a say in matters concerning local road building of kindergarten – so what?

Last year, a local council member of Høyre (“Right”) said something like “This is about security. Thus, we can not make any compromise.”

It would be interesting to know more about where politicians from the quoted local council member up to Minister of justice Emilie Enger Mehl see Norwegian security threatened.

Let’s just assume they would be able to give a convincing answert to this question (noting that nothing points to this actually being the case): the current decision is, at best, preventive. As mentioned, there is currently exactly one local council member who is not Norwegian, and nothing points towards an increasing trend of international diversity in Lokalstyre.

For this preventive measure, the Norwegian government is willing to pay a high price – or rather, to let others pay the price: the exclusion of a large group from local democracy. Many of those feel like second class citizens now.

Norwegian politicians usually not let an opportunity pass unused to point out that Svalbard and Longyearbyen are Norwegian (and I haven’t heard anyone questioning this, with some exceptions of bizarre claims made by Sovjet/Russian politicians, but that’s a totally different issue and by no means relevent in a local democracy context). But suddenly, Longyearbyen is not Norwegian enough to give those who have been living there for years good knowledge of the Norwegian political framework for Svalbard policy? That is, in my opinion, bizarre.

Justizministerin Mehl said (author’s translation): “Nobody is excluded from the democratic process, but you must have lived on the mainland for 3 years to be elected into Lokalstyre.” (Svalbardposten).

It is hard to say what is more worrying. That the government plainly ignores most of the opinions being raised during the public hearing – the voices from Longyearbyen where by far singing the same song of democracy and political participation.

Or that Mehl pretends that nobody is excluded from the democratic process while this is exactly what happens, which is either a concerning lack of knowledge or plainly false. There are very few non-Norwegian inhabitants of Longyearbyen who have spent at least 3 years as registered inhabitants of a mainland community. And the desire to do this has probably not grown for many whom the Norwegian government has now given the finger. This may be perceived as a strong description of the recent decision, but this is exactly how those who are directly concerned may well feel about it (so does this author, in any case).

Which other modern, democratic, European country has retreived lcoal voting rights from foreign inhabitants who used to have these rights before, some for many years? This decision apperas politically disgusting, right-wing nationalist and xenophobic. With this decision, the Norwegian government has joined a circle of European governemnts where, I am sure, they do not wish to see themselves.

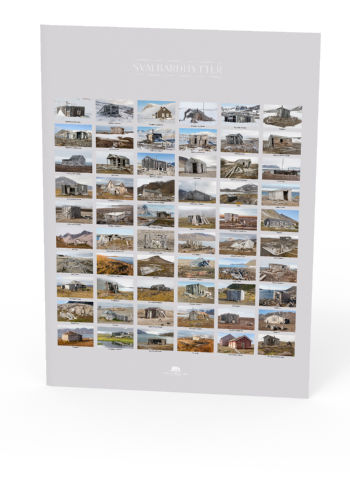

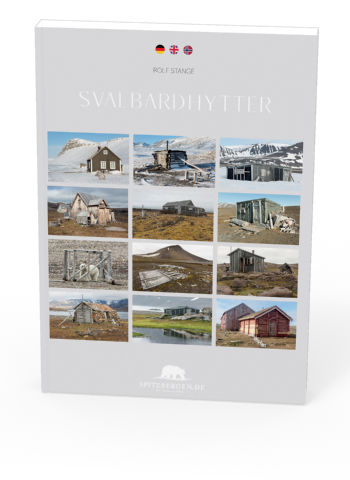

BOOKS, CALENDAR, POSTCARDS AND MORE

This and other publishing products of the Spitsbergen publishing house in the Spitsbergen-Shop.

last modification: 2022-06-19 ·

copyright: Rolf Stange