-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Page Structure

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

-

Newsletter

| Guidebook: Spitsbergen-Svalbard |

Home → February, 2019

Monthly Archives: February 2019 − News & Stories

Grounded trawler Northguider: recovery planned in August

The shrimp trawler Northguider ran aground in Hinlopenstrait close to Sparreneset on Nordaustland, just south of Murchisonfjord. The whole crew could be saved by helicopter, as reported earlier. The crew has later described the whole experience, in total darkness, strong cold and stormy wind, as very dramatic.

Fishing trawler Northguider grounded in Hinlopenstretet, close to the coast of Nordaustland. Photo: Kystverket.

300 tons of diesel and other environmentally dangerous substances and goods could be salvaged in January, but the Northguider is still sitting on rocks. Experts from Sjøfartsdirektoratet, the Norwegian shipping authority, judge her position as stable. The advantage of that is that forces of nature such as wind, currents and ice are unlikely to push the ship into deeper waters. The disadvantage is that also human efforts to salvage the grounded ship will require considerable efforts and a major operation. It is estimated that the salvaging operation will take several weeks of work on the scene.

The Sysselmannen, as the authority who is generally responsible for the management of the area in question, and the Sjøfartsdirektorat and the Kystvakt (coast guard) have now decided that the salvation work will be carried out in August. At that time, the general conditions regarding weather, ice and light should be most favourable.

The coast guard vessel KV Svalbard is currently on her way to the accident site to assess the situation there again, double-checking that there are no environmentally harmful substances and items are on board anymore and that the position of the Northguider is stable. Further monitoring is planned by motion detectors and beacons sendung the position of the ship in case of any unexpected movements.

Arctic winter light in Tempelfjord

Thu

21 Feb

2019

Some visit a temple to find enlightenment.

We visit Tempelfjord and find the light.

View through Eskerdalen, Sassendalen in the distance

in the dawn of the early polar day in February.

The start of our little excursion was admittedly a bit bumpy. First we had to drag a car out of a deep snow hole that a supposed turning around area had turned out to be. It was not the first time that f§/%!”=g hole has fooled someone. We should put up a sign …

View over outer Tempelfjord towards Isfjord.

Also the snow mobiles don’t want to do what we want them to do, something these things quite often do. But finally we are off and on the road. It is a bit fresh today, well below -20°C around Longyearbyen and certainly not far from -30 in Sassendalen and Tempelfjord. A colleage who was on the east coast today said later that he estimated the air temperature on the glaciers around -40°C … as mentioned, it is fresh today.

View from Fjordnibba into Tempelfjord.

It is not just the air that is icy, so are the fjords as well. There is a continuous layer of ice stretching from Fredheim into Tempelfjord. Also Sassenfjord – the continuation of Tempelfjord towards Isfjord – shows clear signs of freezing. If this only continued! We will see what happens the next weeks.

Lukas enjoys the amazing views over Tempelfjord.

After enjoying the amazing views from the little mountain Fjordnibba, we make a little excursion to Fredheim, the famous hut built by the even more famous trapper Hilmar Nøis. He started building Fredheim in 1924 and turned it into a real home during the years to come. In 2015, Fredheim was moved a few metres higher up and away from the coast that was slowly appraching the historical huts due to coastal erosion.

Fredheim, the hut built by Hilmar Nøis, in its new location.

We enjoy the place, the great scenery, the cold, the ice, the light and last but not least some hot soup for a while before we start moving back home. The days are still short, but it is amazing how quickly the light is coming back.

Ice on the shore of Tempelfjord.

Sunshine and 20 degrees …

Mon

18 Feb

2019

… is not really what you expect in Spitsbergen in February.

But it is also not really a good description of what we currently have in Longyearbyen.

Theoretically, we should have had the first sunrise on Saturday (16 February). This does not mean that you can see the sun from Longyearbyen. You would have to climb one of the higher mountains such as Trollsteinen, something that is actually quite popular on that very day.

But it was cloudy, so a tour somewhere in the nearby valleys was a good thing.

Moonlight tour with dogs in Adventdalen.

Today (Monday) was the first really clear day. The grey snow clouds gave way to the clear sky during the morning. The blue light of the late polar night is now giving way to the pink-blue light of the early polar day, at least around noon.

So today we could see the sun again – at least indirectly. It won’t be before 08 March that you can see the sun directly in Longyearbyen again, something that will be celebrated duly. But the mountains are now getting beautiful crowns of pink-orange glowing light now for a while around mid-day.

First sunlight on Hiorthfellet.

The sun remained above the horizon for quite some time, casting her beautiful light over the mountain tops for the first time in months, while the moon is climbing over the peaks.

Yes, and we do have 20 degrees (centigrade) and even more. Below zero, of course!

The moon next to Adventtoppen.

Lunckefjellet: the end of an arctic coal mine

The Lunckefjellet coal mine is a political-economical phenomenon. The first ton of coal was “produced” in November 2013 – a symbolic act, the mine was not yet in productive operation. This was not the case either when Lunckefjellet was officially opened on 25 February 2014, but the mine was “ready to go”. Many thought production would start now big-time, as the mine had until then cost more than 1 billion Norwegian crowns (more than 100 million Euro) and it was there and ready to start production.

Scientists on the way to the Lunckefjellet coal mine.

But this was not to happen. The coal prices on the world markets dropped and the mines of Sveagruva, the Norwegian mining settlement in Van Mijenfjord, went into standby operation just to make sure they would not become inaccessible and mining could start one day – if this decisions was made.

Sveagruva: Norwegian coal mining settlement (Swedish foundation in 1917) in Van Mijenfjord.

In the fall of 2017, the Norwegian government put their foot down. Being the 100 % owner of the Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani (SNSK), the company that owns and runs all Norwegian coal mines in Spitsbergen, the government could directly decide about the fate of mining and miners in Sveagruva and Longyearbyen and related economies. The decision in 2017 was to put an end to all mining in Sveagruva. Both the coal mine Svea Nord, which had been profitable for a number of years, and the new mine in Lunckefjellet were to be phased out and physically cleaned up as far as possible. And the same was to happen for the settlement Sveagruva itself. Norwegian coal mining in Spitsbergen is only continued now in mine 7 near Longyearbyen (where the operation has since increase from one shift to two shifts).

Day facilities and mine entrance at Lunckefjellet.

The reasons were officially said to be entirely economical considerations. The government does not really give more information than necessary, relevant documents have been declared confidential. Many see the end of coal mining in Sveagruva, especially in the newly built Lunckefjellet mine, with a tear in their eyes, as tradition, jobs and an industry that is important for Longyearbyen are about to get lost.

The end of coal mining in Spitsbergen does not come as a total surprise, everybody knew it would come one not too far day. Other branches are developed, with science, education and tourism high up on the list. Nevertheless, Longyearbyen would not exist without coal mining and mining has been the main activity here for most of the history so far. Many people have an emotional connection to mining and quite a few still have a real one, directly or indirectly, and losing coal mining will hurt them economically.

The government was not interested in discussing offers from investors to continue mining in Lunckefjellet, which was never intended to last for more than maybe 7-8 years anyway. This does not add to the credibility of the official reasoning for closing of the Lunckefjellet mine being solely based on the difficult economy.

Tunnel of the coal mine in Lunckefjellet.

The coal mine in Lunckefjellet will be closed soon. The ventilation system is currently being dismantled, and once that is not operative anymore, only specialists with self-contained breathing apparatus could, theoretically, still enter the mine – for a short period, until the roof has become mechanically unstable. This will not take a lot of time. The Lunckefjellet mine will soon be as difficult to reach as the far side of the moon.

Device to monitor rock movements in the roof of the mine.

Bolts to secure the roof are exposed to permanent erosion and mechanical stress. If they are not regularly controlled and serviced a coal mine soon becomes a very dangerous place.

Last week (5-7 February 2019), geologists from the mining company Store Norske and UNIS took literally the last chance to take samples from the coal seam in Lunckefjellet. The coal geology in Spitsbergen is less well known than one might assume and than geologists would want it to by: nobody really knows what the landscape exactly looked like where the bogs grew that later formed the coal.

Geologist Malte Jochmann at work in Lunckefjellet.

Of course there were bogs, and saltwater from a nearby coast is likely to have been an important factor, at least at certain times. But which role did sweetwater play, lakes and rivers? Why are there sandstone and conglomerate (gravel-bearing sandstone) layers and channel fillings within and just on the edge of the coal seam? What did the sea level do at the nearby coast, what was the influence of tectonics? Were there hills or even mountains in the area, or was the surrounding relief more or less level?

Geologists Malte Jochmann, Maria Jensen and Christopher Marshall at work in the Lunckefjellet mine, inspecting outcrops and potential sampling sites.

A walk through the tunnels of the Lunckefjellet mine produces fascinating views into the geological history, raising questions and answering some of them. The geologists Malte Jochmann (SNSK/UNIS), Maria Jensen (UNIS) and Christopher Marshall (University of Nottingham) had just two days to document outcrops and to take samples which might answer some of these questions in further, detailed investigations involving advanced laboratory methods.

Even inside a mountain you are constantly reminded that you are in the Arctic: the temperature is constantly below zero, and ice crystals are growing on black coal surfaces.

Now the Lunckefjellet mine is about to be closed forever. A lot of equipment has already been removed, soon the mine can not be entered anymore. Also Sveagruva will be subject to a major clean-up, initial work has already begun. There won’t be much left in the end. Some artefacts which are considered having historical value will remain (everything older than 1946 is generally protected in Spitsbergen, the threshold will probably be moved up to 1949 in Sveagruva) and possibly a very few buildings for future use – research? Limited tourism? Nobody knows.

It will not be mining, that is for sure.

Sky of stars on the way back from Sveagruva to Longyearbyen.

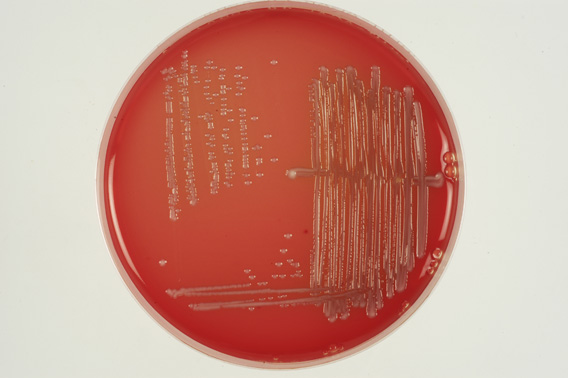

Multiresistant bacteria in Kongsfjord

Bacterial resistance genes that have been found in soil samples in Kongsfjord have recently received considerable media attention. These genes are responsible for multidrug resistance among bacteria. Media and people are asking how such genes could make it into the seemingly untouched nature of the Arctic. Some media see reason for comparison of the recent findings with doomsday scenarios including wars and climate change.

Without any question, the uncontrolled use of antibiotics in many countries and the increasing occurrence of multiresistent bacteria are a very serious problem.

Genes that make bacteria resistent against antibiotics have been found in soil samples taken near Ny-Ålesund in Kongsfjord.

The news about the findings have surprised many, but for scientists, they are not as unexpected as many may believe. This is at least the case with samples that were taken near settlements. The samples in question were taken near Ny-Ålesund in Kongsfjord.

The nature of Spitsbergen is not as untouched as it is often described as, at least not in places like Kongsjord. The settlement of Ny-Ålesund was founded 1916 as a coal mining place as all of today’s settlements in Spitsbergen. Ny-Ålesund became famous in the 1920s when several north pole exepditions were launched there. After mining was abandoned in 1963, Ny-Ålesund developed into an international research village. Today, scientists from many countries come here every years to do fieldwork on all kinds of polar research. Many ships visit the harbour of Ny-Ålesund, including research and supply vessels and cruise ships (smaller ones, crude oil is not allowed in these waters anymore). Kongsfjord is under influence of the Gulf Stream.

According to the original publication Understanding drivers of antibiotic resistance genes in High Arctic soil ecosystems (McCann, C.M., Environment International), all 8 samples were taken close to Ny-Ålesund. The resistence gene NDM-1 (New Dehli Metallo-β-laktamase) was for the first time isolated in 2008 from medical samples from a patient who had previously been treated in a hospital in India. Bacteria harbouring this enzyme are resistent against several groups of antibiotics including one group which is considered last-resort antibiotics.

Klebsiella-pneumoniae (bowel colonising).

NDM-1 was found in this species in 2008.

Further investigations showed that bacteria with this resistence gene are widespread especially on the Indian sub-continent, but they have also been found in countries such as Japan, China, Australia and Canada as well as European countries including the UK, Belgium, France, Austria, Germany, Norway and Sweden. Humans can be colonised by such bacteria in their body, usually in the intestines, without necessarily being sick.

Hence, it is not hard to imagine that bacteria are spread over large distances and into remote parts of the Earth, wherever people settle and travel in numbers. Transportation mechanisms are manifold. Bacteria that travel in human intestines can easily enter the environment via sewage water systems. Animals are bacterial carriers, something that is well-described in connection with migrating birds. These acquire bacteria for example in the wintering areas and transport them to the breeding areas. Kongsfjord is an important breeding area for several migrating bird species such as geese that winter in northern central Europe.

The authors of the original publication (see above) conclude rightly that the findings of the resistence gene NDM-1 in Kongsfjord does not pose any threat on the health for people in the area. But it shows that resistent bacteria that may have originated in connection with uncontrolled use of antibiotics in any one of many countries in the world may spread quickly around the globe. This in itself is not much of a surprise. No matter how sad the distribution of resistence genes into remote (but not untouched) corners of the globe as Spitsbergen is and how dramatic the consequences of infections with such pathogens can be for patients – evidence for the existence of such genes in soil samples taken close to a settlement in the Arctic does not increase any of these problems, but shows that they do not respect boundaries or distances. The dramatic headlines of many recent media supports and comparison to apocalyptic scenarions such as wars do not do the complexity of the problem any justice.

It would be interesting to make a study with samples from areas that are indeed mostly untouched by humans, such as remote and rarely visited parts of Nordaustland.

Text: Dr. Kristina Hochauf-Stange (med. microbiologist)

Climate Report Spitsbergen 2100: Concern and Many Questions

The information that global warming will hardly affect and change any region of the world as strongly as the Arctic is anything but new. Nevertheless, the audience became silent when the climate report “Climate in Svalbard 2100” was presented last Monday at a well-attended citizens’ meeting at the University of Longyearbyen.

The result of the report: An average temperature increase by seven to ten degrees by the year 2100, significantly more and more intensive rainfall, melting glaciers, thawing permafrost soils, the retreat of sea ice and a shorter winter could probably radically change the everyday life of humans and nature on Svalbard within only two generations. Avalanches and mudslides would increase, the water in the rivers would rise and the height of the glaciers would fall by more than two metres per year.

What sounds like the gloomy horror scenario of a bad thriller is actually a report brought up by the Norwegian Climate Service Centre for the Ministry of the Environment, backed by well-respected institutions from the fields of meteorology, energy and polar research. In this report, the researchers formulate forecasts in case that the goals of the Paris Climate Conference of 2015 are not going to be achieved.

The average temperature on Spitsbergen has already risen by two degrees compared to pre-industrial times, and this is in fact noticeable. Reports of temperature records have been accumulating in recent years. The winter of 2012, for example, is likely to be remembered by most inhabitants, when rain, floods and glaze ice in January reminded more of an average autumn day in northern Germany rather than a polar winter in the northernmost city in the world, around 1000 kilometres from the North Pole. Last year, too, there were plus degrees and rain in Longyearbyen in January, and since 2010 there has been no winter with temperatures below the usual averages.

The paradox is that Svalbard itself makes a considerable contribution to this development. The settlements are supplied with energy by coal power, the energy source that blows the most CO2 into the atmosphere. Besides coal mining, tourism is the most important employer on Spitsbergen. But tourists who travel to Spitsbergen primarily use the two most greenhouse gas-intensive means of transport, air travel and cruise ships. And also the locals use mostly airplanes and snowmobiles or cars powered by combustion engines.

At the meeting, possible actions that Svalbard could take to help achieve Norway’s climate goals and limit global warming were discussed rather half-heartedly. Reduce the number of flights to and from Spitsbergen? Switch to renewable energy production? Neither the head of administration Hege Walør, nor Sysselmannen Kjerstin Askholt had answers to these questions.

However Community Council Arild Olsen came up with the radical idea to make Longyearbyen Norway’s first zero-emission community.

Whether this is realistic remains to be seen. Hardly anyone denies, however, that adaptation to climate change is urgently needed, will cost a lot of money and could possibly lead to changes in legislation.

In December 2015, temperatures of up to nine degrees plus again caused thaw and flooding. This river in Bolterdalen is normally dry and frozen in winter.

Sources: Svalbardposten, Climate Report: “Climate in Svalbard 2100”

A day in Spitsbergen: polar dogs and polar jazz

Sun

3 Feb

2019

The experiences to be made here in Spitsbergen in one day can be very rich in contrast: a little ski tour in Adventdalen with company on four legs brings exercise, fresh air and impressions of light and landscape – pure pleasure. For all involved, with two and for legs.

With ski and dogs Adventdalen.

A few hours later you may find yourself in an old hall which belongs to mine 3. No coal is mined in mine 3 anymore, after years of silence it is now regularly used as a mining museum and occasionally for events. Today, there is one of the last concerts of this year’s Polarjazz festival going on here. An experimental Spitsbergen-Jazz-opera – does that make sense? 🙂 The title is “Spor” (tracks) and it combines stories, impressions and emotions from the history and nature, hunting and mining in Spitsbergen. All of that is put into music and sounds by a trio, in major parts with the additional voal powers of the Store Norske Mannskor, resulting in sounds that vary from spheric/experimental through jazzy to groovy.

Polarjazz 2019: ‘Spor’ in Mine 3.

The atmosphere of the event was certainly even increased by the location.

Ban on motorised traffic on fjord ice under discussion

The solid ice in Spitsbergen’s fjord is an important habitat for wildlife as well as a popular destination for both locals and tourists – if it is solid enough. This has not always been the case anymore in recent years. Climate change is happening.

This is where Ringed seals give birth to their pups and Polar bears go hunting.

In earlier times, humans went hunting on fjord ice, today they enjoy the stunning scenery and the wildlife that may be present. In the past – many, many years ago – there was a handful of trappers, explorers and a few locals who went out for a trip on the ice in the remote, lonesome fjords. Because of some duty or to enjoy a beautiful day in the arctic.

Fjord ice: important habitat for seals and Polar bears.

Today, some of the fjords are not so remote and lonesome anymore. Tourists have discovered the Arctic as a fascinating destination decades ago, and snow mobiles make it much easier to cover greater distances. The fjord ice in Tempelfjord and on the east coast of Spitsbergen has been a very popular area to visit for both locals and tourists, mostly coming with organised groups, for many years.

This might change radically in the future. Already in 2018 the fjord ice in Tempelfjord, Billefjord and Rindersbukta (near Sveagruva) was closed in April until the end of season on a rather short notice for motorised traffic. The same measure is now discussed well in advanced. Nobody knows currently if the fjord ice will be solid enough in a few weeks from now when the season really starts.

In contrast to last year’s traffic ban, which was imposed on a relatively short notice, a public hearing is now initiated by the Sysselmannen. The idea is to give those who are concerned a chance to have their word and to make sure everybody is aware of the development. The latter may actually be the more important factor: the Sysselmannen has already made it clear that traffic bans can be imposed, if required for any reason, at any time without any changes of the legal framework.

Popular destination for both locals and tourists: Fjord ice.

A lively debate about this measure is now to be expected. Such a measure would indeed be experienced as drastic by those who have been active in tourism and by many locals. On the other hand, there have been occasions where wildlife was disturbed by motorised traffic, and arctic tourism is a natural target for international environmentalists.

Some require more far-reaching rights for locals than for tourists, a principle that is already used in existing regulations for snow mobile traffic out in the field in Spitsbergen. If this will apply in any future changes of legislation is currently unclear.

Under discussion are the seasonal fjord ice areas in Tempelfjord, Billefjord, Rindersbukta and on the east coast between Mohnbukta and Negribreen. Crossings of the fjord ice in these areas may, at least partly, still be permitted on the shortest possible way in order to enable groups to follow frequently used routes. This concerns mainly the traditional route between Longyearbyen and Pyramiden. But driving elsewhere on the fjord ice would not be possible anymore.

There is, so far, only mention of a ban on motorised traffic (snow mobiles). Skiing and dog sledging are not concerned.

News-Listing live generated at 2025/May/02 at 22:01:31 Uhr (GMT+1)