-

current

recommendations- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

- New Spitsbergen guidebook

The new edition of my Spitsbergen guidebook is out and available now!

- Liefdefjord

New page dedicated to one of Spitsbergen's most beautiful fjords. Background information and many photos.

Page Structure

-

Spitsbergen-News

- Select Month

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- November 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- April 2000

- Select Month

-

weather information

-

Newsletter

| Guidebook: Spitsbergen-Svalbard |

Home →

Yearly Archives: 2024 − News

A little Christmas present: new Spitsbergen pages

P.S. TLDR? Too long, don’t feel like reading, rather get straight to the point? At the bottom of the post are the links to the new pages: Akseløya, Midterhukhamna and the old mines on the north side of Adventfjord.

The last few weeks have once again been jam-packed, but it was worth it, working on the new edition of the Spitsbergen guidebook. More on this in a few weeks from now.

Polar night atmosphere in Adventdalen.

The picture shows the illuminated corner station of the old coal-fired cable car at Endalen.

At the same time, I have been working on a couple of pages dedicated to certain areas and individual locations on Spitsbergen. After all, that’s where you can travel online, getting to fantastic places with just a mouseclick which otherwise are difficult to reach, if at all.

Hint of a northern light over Longyearbyen.

These include, among others, four pages that together illustrate the largest more or less contiguous monument of industrial history in Spitsbergen, namely the mining landscape from the early 20th century on the north side of Adventfjord:

- Advent City was the first ever attempt on Spitsbergen to mine coal industrially.

- Hiorthhamn followed a few years later and is one of Svalbard’s most remarkable cultural monuments from the pioneering days of coal mining with its shoreline complex.

- Sneheim is the old mine belonging to Hiorthhamn. At an altitude of 582 metres on Hiorthfjellet, incredible!

- The old mess and accommodation area “Ørneredet” is part of the Sneheim mine, the old mine belonging to Hiorthhamn.

Also new are the pages about Russeltvedtodden (ever heard of that?) at the southern end of Akseløya (ah of course … the beautiful Akseløya in Bellsund) and Midterhukhamna. And there are brand new pages dedicated to Sassenfjord respectively Tempelfjord. Oh yes, don’t forget a quick trip to Agardhbukta on the east coast 🙂

The moon above the old cable car centre in Longyearbyen.

Climate change in Svalbard’s fjords and the Arctic Ocean

A few weeks ago, I wrote about Record melting of Svalbard’s glaciers in 2024, on this site, focussing on consequences of climate change on land.

But of course the changes are not limited to the land; the sea is also affected. Or, perhaps more accurately, it plays a major, driving role.

The Gulf Stream

In the North Atlantic, much is known to depend on the Gulf Stream. With its comparatively warm water masses, it brings enormous amounts of heat from the south and thus ensures the relatively mild climate in the highest latitudes such as 78 degrees north, where the Isfjord today remains largely ice-free all year round, while some fjords in northernmost Greenland or Canada (Ellesmere Island) only become ice-free briefly in summer or not at all.

Even small changes in the Gulf Stream have a massive impact on the regional climate in the north-east Atlantic. If the Gulf Stream brings a little more warm water or if the water is a little warmer, the North Atlantic will become considerably warmer. If the supply of warm water decreases or no longer reaches as far north, a regional cooling could also occur that could affect the whole of north-west Europe. In the long term, this scenario cannot be ruled out as part of climate change, but the opposite is currently the case.

Kongsfjord

Jørgen Berge from the University of Tromsø has been keeping a close eye on Kongsfjord for more than 20 years. As the research settlement of Ny-Ålesund is located in Kongsfjord, this fjord has been studied closely for a long time, with decades of data available on all kinds of details. In addition, the fjord is located on the part of the west coast that is most strongly influenced by the Gulf Stream, so it can serve as an early warning system for changes in these currents and their local effects.

Kongsfjord near Ny-Ålesund: an oceanographic and marine biology research laboratory.

Berge told Barentsobserver about his work and observations. The result anticipated: a ‘radical change in the marine ecosystem.’

According to Berge, the water masses in the Kongsfjord are warming by 0.1 degrees per year across the entire water column, i.e. by no less than 2 degrees in just 20 years. Two degrees is quite enough to drastically change the oceanographic-ecological character of a sea area – and the warming does not stop. The character of the Kongsfjord has changed from ‘arctic’ to ‘Atlantic’ during this time. In oceanographic terms, this initially means that the water is warmer and saltier.

The ecosystem: plankton and seabirds

Of course, this is not without consequences for the ecosystem. High-arctic, fat-rich plankton such as the copepod Calanus glacialis is increasingly being displaced by its subarctic and less fat-rich relatives Calanus finnmarchicus and Calanus hyperboreus, which has consequences for seabirds that feed on plankton. The high Arctic Little auks in particular, which used to be – and still are, as of now – very numerous, prefer to feed on the energy-rich Calanus glacialis. If they have to rely more and more on their less energy-rich relatives, their diet will become increasingly problematic.

Little auks on the west coast of Spitsbergen.

Recent history shows that the breeding populations of seabirds are shrinking almost everywhere in the North Atlantic. The little auks still seem to be doing quite well, but it is very difficult to count these very small birds that breed invisibly under rocks. The case is clear for guillemots, puffins and gulls, where some colonies in northern Norway have practically collapsed since the 1980s. Disappeared.

Fjord ice: ringed seals and harbour seals

Another aspect is that the Kongsfjord has hardly frozen over for around 15 years. Ringed seals, once the most numerous seals in the fjords of Spitsbergen, need the fjord ice in spring to give birth to their young and to rest. The harbour seal, which is also known from the southern North Sea, is now much more common on the west coast of Svalbard than the ringed seal, which is very similar in appearance. Seals have been naturally occurring in Svalbard for thousands of years and this observation may be coincidental, but it fits in with the scientifically confirmed development of the fjords from a highly arctic ecosystem to an Atlantic one.

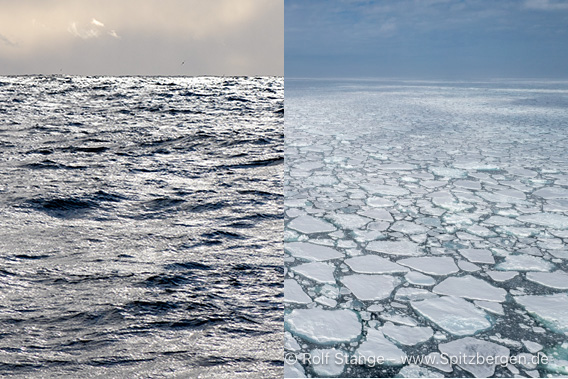

High Arctic ringed seal (left), subarctic harbour seal.

Both live on the west coast of Spitsbergen.

Fish, mussels and temperature records

Berge also speaks of a change in the species composition of fish and mussels. Species such as herring and capelin, which one would not expect to find in high Arctic fjords, are spreading, as are mussels.

More and more common in Svalbard: blue mussels.

Global warming is more noticeable at the poles than at lower latitudes; it is estimated that the Arctic is warming by a factor of three to four more than other regions. If one hopes that climate change can somehow still be limited to a warming of 1.5-2 degrees, then this figure is the global average. For the Arctic, you can multiply that by three or four.

In recent years, record temperatures have been regularly measured in Svalbard, most recently on 11 August at 20.3 degrees, the highest value ever measured on an August day near Longyearbyen.

Even the previously high Arctic fjords in the north-east of Svalbard will not remain unaffected by this development. This is confirmed both by a regular look at the ice map and by personal experience in the fjords of Nordaustland and in Hinlopen Strait, where the previously widespread water temperatures of around 0 degrees are now rather rare and small-scale, especially in the southern Hinlopen Strait and on the southern side of Nordaustland, where the cold East Spitsbergen Current from the Arctic Basin is still exerting its influence. In the northern Hinlopen Strait and in the fjords in the west and north of Nordaustland and up to Sjuøyane, water temperatures of 6-8 degrees are increasingly common, indicating the increasing influence of mild Atlantic water (Gulf Stream).

Rarely ice-free in the past, now regularly in summer:

Fjords on the north coast of Nordaustland.

The Arctic Ocean: from white to blue

The sea ice of the Arctic Ocean is both a victim and a driver of this development. This is one of those feedback effects in the global climate system where the effect reinforces the cause. In this case, an area of water that has become ice-free due to warming no longer reflects the sun’s rays, but absorbs them and converts them into heat, which in turn melts even more ice and even larger areas of water absorb the sun’s rays … and so it goes on.

According to a study recently published in Nature Communications, the Arctic Ocean could become ice-free on a daily basis by around 2030. This study is the first to look at the development on a daily rather than a monthly basis. The Arctic Ocean could therefore be ice-free on a daily basis in a few years’ time if warm winters with little ice formation are followed by warm early summers with high ice loss.

The Arctic Ocean of the future: increasingly blue instead of white.

On the other hand, the study also describes scenarios according to which an ice-free Arctic Ocean will not be observed by the year 2100. Both possibilities are rather extreme scenarios; the real development may lie somewhere in between. Or not, the extreme scenarios are also possible according to the scientific models.

As Jørgen Berge told Barentsobserver: ‘It is likely that the central Arctic Ocean will evolve from a white (ice-covered) ocean to a blue (open water) ocean. What that means, we don’t know.’

Calendar “Spitsbergen & Greenland 2025”: the stories behind the photos

A while ago, I started telling the stories of the pictures in the new photo book ‘Spitsbergen – Cold Beauty’, and I wanted to continue that. Now it is about the new calendar, but the idea is the same: the stories behind the photos, as I’m finally getting round to picking it up again.

The 2025 calendar is a double calendar, Spitsbergen and Greenland are presented with 12 pictures each. Here we have November and December, so four pictures and four stories in total.

Calender “Spitsbergen & Greenland 2025”: November

Autumn in the Arctic – during this time of year, we are hoping for beautiful light. Low sun during daytime and endless sunsets. Of course, the sun doesn’t shine at all in Svalbard in November, as the polar night begins at the end of October. The Spitsbergen picture for the November page was taken on a beautiful day at the end of August 2022, on the first ever circumnavigation of Spitsbergen with sailing ship Meander. The weather was really on our side, and then you can go to crazy places where you wouldn’t normally go. Because they are very exposed, because the waters close to the shore are uncharted and shallow.

This is exactly the case in the extensive Diskobukt on Edgeøya. Here, every wave quickly turns into a breaker even before it reaches the shore, and at low tide the propeller whirls in the mud well before you get anywhere near the coast. It is sensible to stay away from such places in everyday life. But not every day is everyday life, and we are not always sensible, are we 😄 otherwise where would we end up … certainly not in this part of Diskobukta! (This is not about the relatively well known kittiwake colony in the northern part of Diskobukta.) Where we were ashore in the evening of this unforgettable day and went for a little hike to and up a low hill. I had seen this hill so many times from a distance as we sailed past and always thought that one day I would have to go there … and this was just the right opportunity! It just has to happen, you can’t force things like that.

Diskobukta on Edgeøya (not the one in west Greenland) is aptly described as ‘vast’ or ‘wide open’. Barren, high arctic, a vast, darkly coloured alluvial plain. Numerous whale bones add variety to the otherwise monotonous landscape impression, and the great light of a beautiful evening at the end of August at around 78 degrees north did its part.

The November-Spitsbergen-image shows Diskobukta on Edgeøya.

I had been there years before. On that occasion: horizontal snow – and a polar bear on the shore. That was great too. But that evening at the end of August, when we were able to go ashore … unforgettable! That’s the stuff my Spitsbergen dreams are made of. It was so beautiful that I realised on the spot that one of the pictures would be in the calendar as soon as possible. ‘Calendar potential’ is the highest photographic standard here 🙂

The other stories are told relatively quickly. In Scoresbysund in East Greenland, the musk ox is roughly what the polar bear is to Spitsbergen: tourists usually want to see them.

Now they usually stand somewhere far away on a mountain slope. It takes a bit of luck to see them up close. And too close is also potentially unhealthy, of course, especially when you are hiking.

One fine day with early winter mood in September in Rypefjord, deep in Scoresbysund, everything was just right: the musk oxen were quite close to the shore and we could see them perfectly well from the boat – the lovely Ópal from Iceland. And very helpful to secure not only some nice views, but actually good photos: I had my 600 millimetre lens with me, the really big one that usually stays in Spitsbergen and lives on the ship rather than being dragged around on land. Just for the polar bears. Or in Greenland for the musk oxen. The effort was worth it here.

The November-picture for Greenland: Musk oxen in Rypefjord.

Calender “Spitsbergen & Greenland 2025”: December

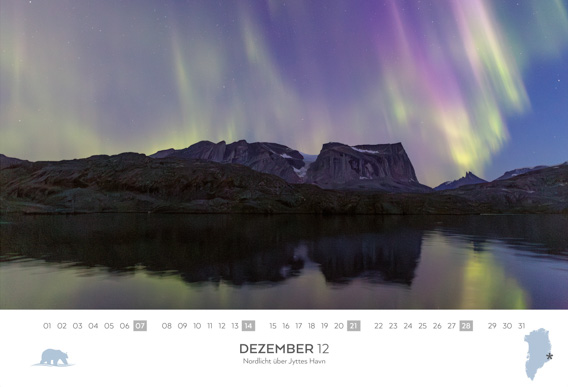

Of course, I wouldn’t miss the northern lights at the end of the year. December is the deepest polar night, and of course, you just can’t get to the most remote corners of Spitsbergen at this time of year. But why should you, you can see the northern lights wonderfully in Adventdalen, not far from Longyearbyen.

The December-image, Spitsbergen: Northern light above Adventdalen.

Large parts of Greenland, including Scoresbysund, are actually even better for observing the northern lights than Svalbard, where you are already north of the hot aurora zone, the Aurora Oval. Scoresbysund is the right place to be, as there is a lot of action when it only gets dark at night. And due to the more southerly location, this is the case earlier in the year than in Svalbard, September is a pretty reliable month. In this picture we see the northern lights over Bjørneøerne, with the magnificent Øfjord and the striking Grundtvigskirke mountain in the background.

The December-picture, Greenland: northern light over Bjørneøerne.

The double calendar ‘Spitsbergen & Greenland 2025’ is available in the Spitzbergen.de webshop in two sizes (A3 and A5), as well as many other great things – not just books – of course.

Advent season in Longyearbyen

Now, Longyearbyen is located in Adventfjord, isn’t it 🤪😵💫 this is actually not only one of my infamous puns, but actually a not so rare misunderstanding. The name Adventfjord has nothing to do with the Advent season, but with an English whaling ship, the Adventure, which was there in the 17th century.

But that’s not what this is all about, it’s about the start of the Advent season in Longyearbyen. There is also a Christmas market here, or rather two, even. However, they are a little different to what most of us may be used to. On two weekends, in mid-November and last weekend, the hard-working and creative artists, craftspeople and everyone in between set up their stalls, first in the cultural centre (Kulturhuset) in the town centre and on the first weekend of Advent in the artists’ centre (kunstnersentrum) in Nybyen higher up in the valley, where the gallery used to be some years ago. Unfortunately no roasted almonds and no mulled wine, but lots of great handicrafts made in Longyearbyen, including Eva Grøndal from the local photographer dynasty of the same name (first picture) and Wolfgang Hübner-Zach from the carpentry workshop Alt i 3 (that’s where the beautiful kitchen boards and driftwood picture frames come from 😉). And lots of other great things. Lena’s deceptively real chocolate fossils, awesome! To name just one more example.

Christmas market in Nybyen

- gallery anchor link: #gallery_3402

Click on thumbnail to open an enlarged version of the specific photo.

And then, of course, there is the traditional torchlight procession on the afternoon of the first Sunday in Advent – it is dark, even the street lights are switched off in the area during the event – from the Huset to Santa’s letterbox below the old pit 2b, the ‘julenissegruve’ (Santa’s pit). Father Christmas is working hard up there now, so this old coal mine, abandoned since 1964, is now lit up again until Christmas. And down by the road is the letterbox where the children (including the older ones, if they want to) post their letters to Father Christmas with all their wishes.

The route continues to the centre, where the Christmas tree is lit. Of course, there are warm words, cheerful singing and good cheer and, last but not least, Father Christmas arrives with his assistants and distributes a small advance to the many children.

The Christmas tree is lit

- gallery anchor link: #gallery_3405

Click on thumbnail to open an enlarged version of the specific photo.

This marks the start of the Advent season in Longyearbyen, and everywhere else too, of course. I wish everyone a happy and joyful Advent season!

Record melting of Svalbard’s glaciers in 2024

It will hardly surprise anyone, considering the warm summer with new temperature records, such as the warmest temperature ever measured in Svalbard in August: the arctic glaciers have suffered massively this year. Especially in Svalbard, where climate change is happening seven (!) times faster than the global average, as glaciologist Emma Wadham from the University of Tromsø told the Barents Observer. Just on 23 July 2024, a record-warm day, the glaciers lost 55 millimetres of water equivalent or five times the normal value, according to climatologist Xavier Fettweis from the University of Liège, who analysed satellite images. And that was just one day in a week-long period in which temperatures were on average around 4 degrees above the long-term average for this period.

Meltwater on a glacier surface.

The trend towards melting is particularly pronounced in Svalbard, but it is present throughout the Arctic. The loss of ice on land in turn has feedback effects on the climate: land absorbs more solar radiation than ice and snow and therefore warms up even faster; to a lesser extent, this also applies to exposed ice compared to snow.

Edge of a small ice cap on Storøya in northeast Svalbard. Numerous small meltwater channels are visible on the surface of the ice cap. Wet firn and exposed ice absorb more solar radiation than dry, white snow, which leads to increased melting. The ice-free land that is now exposed next to the ice cap is also better able to convert solar radiation into heat.

The impact on the marine ecosystem is yet another issue: increasing amounts of sediment-laden meltwater are flowing into the previously mostly clear water of the fjords and coastal waters. Due to its sediment load, the meltwater is murky and opaque, allowing little light to pass through. This in turn has an impact on algae growth, which is dependent on light for photosynthesis.

Meltwater with sediment load at Monacobreen in Liefdefjord.

But the changes of the marine ecosystem of the Arctic are another story. More about that later.

New “Svalbardmelding”: Svalbard-strategy for the next years

On Thursday (November 21) the Norwegian Parliament in Oslo, the Storting, has passed the new Svalbardmelding angenommen. The Svalbardmelding is a government strategy paper that outlines the Svalbard politics for the next 5-10 years. It includes thus no concrete legal measures but rather a set of intentions and ideas which have to be discussed and turned into laws in the future.

Let’s take a step back. Norwegian Svalbard politics is based on the following five principles:

- A consistent, constant maintenance of Norwegian sovereignty.

- Compliance with the Svalbard Treaty and monitoring its implementation.

- Maintaining calm and stability.

- Protection of the region’s nature.

- Maintainance of a Norwegian population.

Norwegian flags in Longyearbyen (on the Norwegian national day on 17 May): Longyearbyen and all of Svalbard are and will remain Norwegian. But the government would prefer to have a higher proportion of Norwegians amongst Longyearbyen’s population. Sysselmester Lars Fause (front right) is the highest representative of the Norwegian government on site.

And what’s in it?

Quite a lot, the document has more than 80 pages. You can download it on the government’s website.

And the government has already implemented several major legal projects in the recent past, including a reform of the local electoral law that cost many foreign voters their local voting rights. The new rules for tourists that come into force on 01 January, 2025 are another important new set of legislation. Energy and housing are other important topics that have been worked on for years already on various levels, see below.

Some important points of the new Svalbardmelding:

Mental health

There are people with mental health problems all over the world and Svalbard is of course no exception. However, those who are confronted with acute mental health problems in Longyearbyen have very limited access to professional help. This may have cost two people their lives in the recent past: there have been two suicides in Longyearbyen in 2023.

It is mainly thanks to the commitment of Longyearbyen’s political youth that the government wants to improve this situation, but according to them, applaude is not due before a psychologist is actually installed in Longyearbyen, according to NRK.

Airfreight

This is not about same day delivery to the final consumer. But a supply of goods of all kinds, including fresh produce according to modern standards, should be available in Longyearbyen all year round. There had been some discussion and uncertainty surrounding the Norwegian Post’s freight flights to Longyearbyen. Now the government is providing money to maintain freight flight logistics, which of course involve more than just apples and bananas. However, it remains to be seen how this will be organised in the long term.

Empty shelves in Svalbardbutikken (Coop Svalbard) in Longyearbyen:

not unheard of, but undesired.

Low taxes

Svalbard is and shall continue to be a low-tax area. The background to this lies in the Svalbard Treaty; in short, Norway as a state should not benefit from taxes and duties. Therefore, there is no VAT on Svalbard and other taxes and duties are also often lower than on the mainland. This should generally stay as it is, but adjustments are possible.

Housing and population

Things are likely to get much more exciting for many here. The government wants to freeze the size of Longyearbyen at the level before the deadly avalanche on 19 December 2015, and Longyearbyen should not grow beyond that. And the government wants the Norwegian share of the population to increase.

House building in Longyearbyen. The impression that the town is growing is wrong:

it is about replacing what has been lost since 2015.

According to the Norwegian Central Statistical Office (SSB), 2595 people currently live in Longyearbyen and Ny-Ålesund, including 1621 Norwegians, i.e. around 63%. The latter is not enough for the government. In fact, the proportion of Norwegians in the population has been falling for years, which is partly due to the closure of Norwegian coal mines in Sveagruva and Longyearbyen: In these well-paid and previously secure industrial jobs, a high proportion of the workforce was Norwegian. The strategy formulated in earlier Svalbard strategy papers of replacing mining with higher education, research and tourism has proved to be counterproductive from the government’s point of view, as the jobs in these areas are much more international than those in mining. The government wants to take countermeasures here (comment: the rules that come into force on 1 January 2025 should also be seen in this light; the political disappointment over the relatively low Norwegian share of the jobs created in tourism is likely to be at least as important as environmental protection, which is probably more of a pretext here). End of comment).

Housing policy, which has long been a hot topic in Longyearbyen, which is characterised by a housing shortage, has been a tool used by the government for a while now to increase the Norwegian share of the total population: Even though the overall supply of housing is not expected to exceed the 2015 level, the restructuring that inevitably occurred after the avalanches in 2015 and 2017 (over 100 flats were classified as at risk of avalanches and accordingly demolished) also provides an opportunity to reorganise ownership. The private housing market is being reduced and the proportion of state-owned housing is growing in favour of employees of large, directly or indirectly state/public actors, where the proportion of Norwegian workers is higher than in the service sector, for example. These actors include Lokalstyre (municipal administration), Sysselmester, UNIS, Folkehøgskole (education) and others.

In addition, living in Longyearbyen should remain attractive, especially for the Norwegian population. And there is little doubt that there is need for action here, as the average length of stay in Longyearbyen, which is already characterised by a high level of fluctuation, is falling.

Energy

And what good is the nicest flat if there is no power from the socket and the heating stays cold? It’s not that bad, but the scenario cannot be ruled out in the small town of Longyearbyen, whose energy supply is characterised by the fact that it is not part of a supra-regional grid. The subject of energy has long been a hot topic of discussion in Longyearbyen. On the one hand, it is about the sharp rise in prices for electricity and district heating, but also about security of supply and where energy should come from in the long term. The days of coal as an energy source in Longyearbyen are over and the current diesel power plant fails to fulfil all requirements in terms of security of supply, economic efficiency and climate neutrality. Today’s reality is a far cry from the earlier idea of being a role model on an international level; at the moment, people are happy if the heating is on during the cold months and the electricity is at least halfway affordable, even if the government has to help out with money (subsidised electricity prices) and the military with additional mobile generators.

Whatever the energy supply of the future looks like in Longyearbyen: The state, represented locally by the mining company Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani, will play an increasingly important role.

Visitor fee

The government wants tourists to contribute a higher proportion of public income via a visitor contribution. This contribution would amount to up to 5%, which would be added to hotel stays, for example; ship passengers could be charged a flat rate of 150 kroner, for example. Such a system already exists on the Norwegian mainland, where the revenue goes entirely to the respective municipalities. In Svalbard, the state wants to reserve the right to a portion of the revenue.

Since 2007, Svalbard has had an ‘environmental fee’ (miljøgebyr) of 150 kroner, which is included in flight tickets and paid by ships bringing passengers to Svalbard. This environmental fee is administered by the Svalbard Miljøvernfond, to which anyone in Longyearbyen can apply for financial support for projects with an environmental aspect. The environmental fee is not part of the current discussion, the visitor contribution will come on top of it.

Until this happens, there is certainly need for further discussion, for example with regard to who benefits from the income and what it can be used for.

From Skjervøy to Hamnes

We went up to a viewpoint in Skjervøy in the late afternoon. Even the rain stopped and the view over Skjervøy town and harbour was lovely!

Next day we started for a final round of whalewatching in Kvænangen – not without some success 🙂 – and then set course for Hamnes, one of few places in the wide area that was not destroyed by German troops in 1944/45 and hence has some of its historical charme preserved.

We went for a little walk in Hamnes and then enjoyed Captain’s Dinner on board. Piet and the service crew had really gone “all in”, making a wonderful (and very tasty) evening possible for everybody!

And as Captain Douwe described the trip, summarised in my own short words: “the worst weather, the best whales”. Yes, there is some truth in that …

Photo gallery Skjervøy, Kvænangen and Hamnes – 17th November 2024

- gallery anchor link: #gallery_3396

Click on thumbnail to open an enlarged version of the specific photo.

Kvænangen: whales, whales …

Waiting the weather out in Manndalen turned out to be a good thing. Well, Manndalen was in itself more than just worth a visit anyway, but now we have Kvænangen in reasonably calm conditions. A bit of swell, but almost no wind.

What can I say? It didn’t take more than half an hour until we saw the first orcas. Not much later followed some Fin whales. And then humpback whales. Many of them. Stunning. What a day! Just have a look at the pictures. It went on for hours, wherever we went.

In the evening we went along in Reinfjord. „Evening“, however, is a relative term here now. Sunset is at 13:08 hrs …

Photo gallery Kvænangen (1) – 15th November 2024

- gallery anchor link: #gallery_3394

Click on thumbnail to open an enlarged version of the specific photo.

And we continued with the whales on Saturday. Whales are the focus of this voyage, and I would say we are doing well … the weather is not of the greatest sort and some more light would do, but welcome to north Norway in mid November 🐳 😀

Photo gallery Kvænangen (2) – 16th November 2024

- gallery anchor link: #gallery_3395

Click on thumbnail to open an enlarged version of the specific photo.

Manndalen, Manndalen

And again there is a strong low pressure on the way to northern Norway. To avoid strong winds and big waves, we retreated deep into Lyngenfjord, to Manndalen. An interesting place, meeting place of cultures and ethnic groups: Kvens, Sami and ethnic Norwegians have lived here together for centuries, often as a friendly neighbourhood, sometimes less so. There is a very interesting cultural centre/museum in Manndalen dedicated to the Samí people, “Senter for nordiske folk”. Of course we went there.

Later we filled the dark part of the day with lectures and some on board cinema.

Photo gallery Manndalen (1) – 13th November 2024

- gallery anchor link: #gallery_3392

Click on thumbnail to open an enlarged version of the specific photo.

A strong low pressure like the current one needs two days to move trough, so we spent yet another day in Manndalen with snow falling the whole day. We stretched our legs in the morning with some daylight and continued with our lecture series in the afternoon.

Photo gallery Manndalen (2) – 14th November 2024

- gallery anchor link: #gallery_3393

Click on thumbnail to open an enlarged version of the specific photo.

Temperature records and storm in north Norway

Never before have temperatures as high as today’s been measured in north Norway: stations of the Norwegian meteorological service between Vesterålen and Finnmark recorded up to 16 degrees today (8 November), as NRK reports.

A heavy storm is raging over the whole area with winds up to force 11, and there are reports about damage.

Yesterday it had not yet been so crazy, so we sailed out into Kvænangen, in beautiful style under sails, and saw some whales here and some more there. But the wind just kept increasing and I guess there might well have been more than just a few on board who were quite happy when the ship was alongside in Skjervøy again in the later afternoon.

Today we stayed in port. Good thing, considering the conditions with howling gusts which can literally blow one’s socks off. Walking outside is very unpleasant, with sand and small stones being blown into your face. There is the occasional hole in the clouds, but no northern lights so far and now it is raining again.

But we are having a good time. Now I understand why I put quite a lot of time into preparing some new presentations 🙂 and this morning, when it was just a little bit less crazy, we went to one of the hills of Skjervøy.

Photo gallery Kvænangen & Skjervøy – 06th/07th November 2024

- gallery anchor link: #gallery_3375

Click on thumbnail to open an enlarged version of the specific photo.

How are Svalbard’s polar bears really doing? A critical reply from Morten Jørgensen

Svalbard’s polar bears are doing well – the population is stable or even growing slightly, many of the animals are in good physical condition. This is Jon Aars description of the current situation, see previous article.

But there are other opinions. This is Morten Jørgensen’s critical reply to Jon Aars description of the state Svalbard’s polar bears currently are in. Morten Jørgensen is the author of the book Polar bears: beloved and betrayed.

Polar bear on Prins Karls Forland.

Morten Jørgensen’s critical reply to Jon Aars

To the statements made by the leading polar bear researcher at the Norwegian Polar Institute, Jon Aars, as he has been quoted in the article Ekstremår for sjøisen: – Har smeltet raskt gjennom sommeren

I feel compelled to make this comment:

There is a tendency in polar bear management to push the consequences of the many problems that the species face into the future. Sometimes the near future. But never right now. Because that would mean that the hunting would have to stop, and the managers cannot bring themselves to even begin to face that decision. This laissez-faire attitude of projection of today’s issues into the future spills over into science.

Latest, Jon Aars claims that the polar bears in Svalbard for now are doing ok – but will face tougher times in the decades to come. He even goes so far as to say that the local population is stable and may be growing.

He has absolutely no scientific basis for making such statements.

The latest attempt at counting the polar bears of Svalbard led to the conclusion that there is no statistical significant change in the population since the previous “count”. In other words, Jon Aars’ optimism is based not in scientific data, but in … ? I guess only he knows.

Also: The presumed stability of the population, based on the data from those last two counts, is NOT a good sign. It is actually almost evidence that the local polar bear population on Svalbard is in dire straits. How so? Well, the other mainstream mistake which Jon Aars makes is to forget the historical context. If everything was just fine, the local polar bear population in Svalbard should in recent decades have shown, and should still be showing, a significant increase – based on their current local protection status after long periods of extreme over-hunting. The very fact that the population is still lingering at a meager 200-500 or so bears is a clear indication that the disintegration of their main habitat is causing the local population to be under massive stress.

The Svalbard polar bear population is clinging on. And must be presumed to be facing a steep decline soon. To bring forth unfounded optimism is not good science, but only serves to falsely appease those who think that urgent action is not needed for the polar bear to receive full protection.

Morten Jørgensen

October 30, 2024.

Arctic drift ice shrinks, Spitsbergen’s polar bears doing well

The drift is in the Arctic Ocean is shrinking and shrinking, breaking one negative record after the other, but nevertheless, Svalbard’s polar bears are doing well so far – that is, in very short words, the essence of a press release by the Norwegian Meteorological Institute that includes some information provided by Jon Aars, polar bear scientist within the Norwegian Polar Institute.

Drastic sea ice loss

The sea ice in the Arctic Ocean is being lost a a dramatic pace. That is the unequivocal message of a wealth of scientific data, from satellites and other. In 2023, the loss of arctic drift ice amounted to 3 million square kilometres compared to the reference period 1981-2010, and the negative trend is continuing in spite of a good ice winter 2023-24 in Spitsbergen.

Polar bears: the Svalbard population

That has obviously consequences for polar bears. There are approximately 250 polar bears living in the Svalbard archipelago. The number 3000 that is often mentioned in this context refers to the much larger area of Svalbard and Franz Josef Land including surrounding sea areas.

One of approximately 250 polar bears who spend their lives mostly on land in Svalbard.

But Svalbard’s polar bears are doing well despite less ice and shorter periods with frozen fjords and ice-bound coasts. These bears are used to life on land and have, at least to some degree, developed techniques to tap food-sources less dependent on sea ice or fjord ice. There are, for example, those bears that have developed the skill to hunt reindeer.

The local population is stable or even growing slightly, according to Aars, and they are mostly in good physical shape.

Areas traditional used by pregnant females to give birth such as Kong Karls Land and Hopen have lost their significance in this context because of now unreliable ice conditions in these areas. It is believed that these females now use areas further northeast, such as Franz Josef Land in the western Russian arctic.

Polar bears: the oceanic (drift ice) population

This so far stable or even slightly positive development applies to polar bears in Svalbard with a largely land-based way of life. Things may well be different for polar bears following what we might consider a more classical way of life for a polar bear, in the drift ice far from land.

The sun goes, the Blues come

Friday saw this year’s final sunrise and sunset; both were kind of happening at the same time and behind mountains anyway, hence invisible from Longyearbyen. The polar night started on Saturday, the first day without the sun coming above the horizon at all – until mid February! The polar night, almost four months long, is, however, not completely dark. The real dark period (mørketid) won’t start until early December. Until then and in the last weeks of the polar night, there are a couple of hours of twilight mid day. Click here for more about midnight sun and polar night.

The first day without sun: early afternoon at mine 3.

So now, with four months without sun to come, you could indeed get the Blues – and you do these days in Longyearbyen 😎 the Dark Season Blues Festival is happening these days, as every year in late October, when Norwegian and international Blues acts come to Longyearbyen to share the various stages in town.

Dark Season Blues Festival in Longyearbyen. Stein Stokke & the Engine at work in mine 3.

One of these stages is at mine 3 above the airport. Mine 3 used to be a real coal mine, but abandoned in 1996, it is now used as a visitor mine and the surface installations are occasionally used for cultural events. This Saturday, one could enjoy some hearty-hefty Blues there played by Stein Stokke & The Engine, a Blues band with a good name in Norway.

Budget deficit in Longyearbyen

That is definitely something Longyearbyen shares with many other municipalities in Norway and elsewhere: public budgets are under stress, costs are on the rise everywhere and income does not always meet expectations. In Longyearbyen, for example, the communal art gallery Nordover did and does not yield the economic result that had been hoped for. In the past, the gallery used to be in Nybyen (the upper part of Longyearbyen). Now it resides in the same building as the supermarket Svalbardbutikken, with a rather inconspicuous entrance on the building’s northern side that many tourists apparently don’t see (or don’t care much about). When the gallery was in Nybyen, it used to be a popular stop on guided bus tours for cruiseship tourists.

Closing Svalbardhallen (swimming & sports hall) for a longer period last summer because of legionella-loaded water didn’t help either. As a result, a deficit of one million kroner is expected for the sector leisure and culture in 2024 – the largest single deficit in Longyearbyen’s public spendings this year. The total deficit amounts to 5.3 million kroner (ca. 440,000 Euro) in 2024.

Longyearbyen in October 2024: no snow, no money (the latter is not quite true).

Part of the deficit can be accounted for by means of internal restructuring. The highest sum is to be paid by the youngest members of the municipality: the budget of the communal kindergartens is now cut by 500,000 kroner. On the other side, the municipality of Longyearbyen still has a total of 70 million kroner sitting in various bank accounts, as Svalbardposten reports.

As a result, Longyearbyen is still much better off than many municipalities in mainland Norway: for example, Senja (near 15,000 inhabitants) south of Tromsø has to deal with a deficit of 50 million kroner in 2024, Tromsø itself even lacks 259 million kroner in last year’s budget, according to NRK. Until now, the finances of 2023 Norwegian municipalities are under state supervision.

Longyearbyen donates record-breaking amount

The “TV-aksjon” is a big event anywhere in Norway, but in Longyearbyen it is bigger than most other places. It is a charity event created by the Norwegian news platform NRK. In Longyearbyen, it ranges from children knocking on doors to collection money over an open day at school with sales of cake, books, theatre plays and so on to the main event, a charity auction that was held on Sunday (20 October) evening in the culture house.

Private individuals, companies and organisations donated a total of 107 items that were auctioned for a good cause, which this time benefits children with cancer. The good cause is a different one every year.

The “TV-aksjon” in the Culture House in Longyearbyen: an auction supporting a good cause.

The list of items was long and included a good number of very interesting offers. It ranged from small stuff, not necessarily adrenalin-kicking items such as tiepins and cuff links donated by the mining company Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani, over various activities offered by ocal tour operators to exclusive events such as climbing the smoke pipe of the disused coal power plant.

A happy bidder can join the priest on a helicopter flight for a church service at the Polish research station in Hornsund next year for 25,000 kroner.

The probably most exciting sale of the night was the very last item: the fur of a polar bear that was shot last year in Krossfjord. Donated by the Sysselmester, the hammer finally fell at 112,000 kroner (a good 9400 Euro). The hammer in question, by the way, was the famous “Fause-hammer”, donated years ago by Sysselmester Lars Fause after he (Fause) inadvertently had made a hole into a chair leg with an unintended pistol shot. Fause presented himself both honest and humorous, first paying the fine that comes for negligent handling of firearms and then, being auctioneer at a TV aksjon himself years ago, using this hammer that had been crafted from the chair leg in question. This time, the hammer was handled by Ronny Brunvoll, manager of Visit Svalbard.

The polar bear fur was auctioned for 112,000 kroner.

The highest price, however, was paid for a trip to Ny-Ålesund for 10 persons, including flight there and back from Longyearbyen, one night and three course dinner in “Amundsen’s Villa”, then and now representative accommodation for the director of Kings Bay, the state-owned company that owns and runs Ny-Ålesund. The successful bidder put no less than 150,200 kroner on the table. But who wouldn’t love to join on that trip? 🙂

There is some ambition in Longyearbyen to be number one on the list of places regarding donation per capita (resident). Despite of the remarkable sum of 2.5 million kroner, which indeed is a record for Longyearbyen, it wasn’t enough for the number one place of this list, however: this amount corresponds to 1043.62 kroner, less then half of what was given by the community of Rødøy (1139 residents, south of Bodø) with 2311.46 kroner, according to official statistics. Considering absolute numbers, the large cities of Oslo, Bergen and Trondheim (in this order) take the first places anyway. The total sum of this year’s TV aksjon amounts to an impressive 367 million kroner, of which 50 million kroner were given by the Norwegian government.

News-Listing live generated at 2025/May/03 at 13:13:11 Uhr (GMT+1)